Development of the Canadian Icebreaker

I was writing an article that contained a reference to the CCGS Camsell, a Coast Guard icebreaker, and I got to wondering how many people knew about the history of the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) ice breakers. Thanks to the generosity of the CCG website I have been given permission to reproduce their material here. It is a very interesting story.

The following article is reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2012

*******************************

USQUE AD MARE

A History of the Canadian Coast Guard and Marine Services

by Thomas E. Appleton

Development of the Canadian Icebreaker

We have already noted the influence of the Prince Edward Island winter service on the building of passenger vessels able to navigate in ice, ranging from the underpowered and ineffective Northern Light of 1876 to the handsome cruising ship Earl Grey of 1909. The main business of these ships was to maintain communications. While this evolution was unfolding, the problem of flood control on the St. Lawrence demanded attention. From earliest times ice floating down had formed an annual dam between Montreal and Quebec, causing flooding as it built up and further damage to ships when it gave way. In an attempt to control this process by keeping the ice on the move, a requirement now arose for ships whose primary role was to break ice rather than to maintain communications. As a secondary role, which Canadian icebreakers must have to provide an economic year round usage, there was plenty of work to be done in support of aids to navigation.

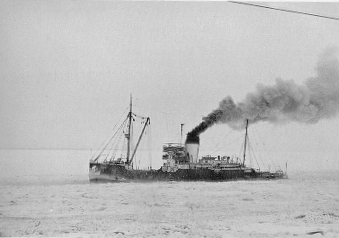

In response to this need, two ships were ordered from Paisley in 1904, the Champlain and Montcalm. The Champlain was a single screw ship of modest size designed to work in and out of ports on the north shore of S. Lawrence, but the Montcalm was the largest and most powerful icebreaker to be commissioned in Canada up till that time, being fitted with machinery of 3,600 horsepower and twin screws. Canadian icebreakers of this period were little different from conventional steamers except for the power of the engines and the strength of the hull. The Montcalm had a cut-away forefoot enabling her to ride up on the ice to some extent but she did not have the rounded form of more modern icebreakers, depending mainly on her ability to back and fill while ramming the ice with her study bows. Some of the old icebreakers even had bilge keels although these were usually damaged or knocked off while in service. It will be recalled that the Montcalm, rolling her way violently to Russia in 1943, was particularly uncomfortable without them. Until the advent of stabilizing devices, all icebreakers were lively in a heavy beam sea.

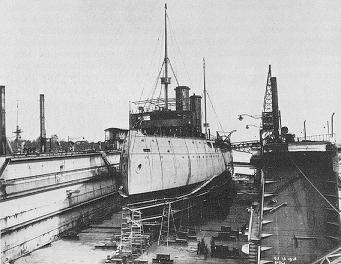

The CGS J. D. Hazen was the first ship of any kind ordered from Canadian Vickers Ltd. On completion in 1916 she was sold to the Russian government who renamed her Mikula Seleaninovitch. After service in the White Sea the vessel fell into French hands in 1919, probably as a prize of war. In 1923 the Canadian government bought her back from a shipbroker in Havre and she served the Department, as the CGS Mikula employed in St. Lawrence icebreaking, until 1937 when she was sold to Liverpool, NS, for breaking-up. This photograph, taken in 1916, shows the Mikula on the blocks of the floating dock Duke of Connaught before sailing for Russia.

(Canadian Vickers Ltd.)

Under the command of Captain Charles Koenig, the Montcalm spent the winter of 1904-05 working in the River and was successful in preventing the usual floods, and as the master was able to report:

“. . . the very fact of a broad channel four miles long, cut through a wall of deep ice, must have let out an immense amount of water.”

This effort was something of a sensation and a Montreal engineer, Percival St. George, who was asked to give his opinion on the work, reported to the Minister of Marine and Fisheries that:

“The work being done by the steamer is marvellous considering the immense thickness of the ice and the enormous power to contend with. If I may suggest anything, I would recommend that another steamer be used in conjunction with the Montcalm so that two steamers could work together, one either side of the channel.”

This was done and a series of steam reciprocating icebreakers followed the Montcalm, differing from each other in power and dimensions, but falling into the same general pre-war category. The Lady Grey (1906) came from an English yard to be followed by the Mikula (1916), Saurel (1929), N. B. McLean (1930) and Ernest Lapointe (1940), all constructed in Canada. These ships collectively carried the brunt of the icebreaking task through two wars and the depression until the advent of the modern generation of icebreakers. The first three were literally worn out in service; the Lady Grey had the added misfortune to sink dramatically after a collision while helping the Quebec ferry in 1955, while the McLean and Ernest Lapointe survive to uphold a tradition of toughness and longevity. During this period the use of oil fuel became general but the Mikula was coal fired which made it difficult for her engines to keep steam under the fluctuating power conditions required for working in ice.

After the second world war, an intensified interest in our northern waters led to improvements in the design of icebreakers. Although it had long been recognized that weight and power are the two most important factors leading to success in breaking ice, the effective use of this power demanded ships which could ride up on the ice without losing stability and which could work themselves free from this position. The modern icebreaker has heeling and trimming tanks so arranged that very large capacity pumps can transfer water ballast from one side of the vessel to another, or from an after trimming tank to a forward one. By this means the vessel can roll about until the surrounding ice is fractured sufficiently to enable the propellers to be effective. With this capability it is important that vertical or concave surfaces be avoided in the hull which must be well rounded under water and deep enough to provide good immersion for the propellers which are placed as low down as possible.

Some of the post war need for icebreakers arose from the natural growth of the Eastern Arctic Patrol which, as we have seen, had progressed from the old wooden ships of exploration to the C.D. Howe by 1950. But by far the greatest impetus was provided by the phase of cold war tension which arose between the western powers and the Soviet Union. This led to the concept of the naval icebreaker for patrol work. When defensive radar installation of the DEW line were built, between 1952 and 1953, an immediate need arose for icebreakers capable of supplying the high Arctic and of supporting supply convoys in the northern Hudson Bay, Foxe Basin and Baffin Island.

Meanwhile the exploitation of Canadian mineral resources, starting with the near at hand areas of Quebec and Labrador, eventually led to the construction of new ports and an increasing traffic in ore carriers in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Here again, to permit economic exploitation, full use had to be made of the navigation season and a pressing need arose for large icebreakers. The combination of winter or end of season work in the Gulf, and summer work in Arctic waters was now to provide, for the first time, a possibility that the largest class of icebreaker, too big to be suitable for the secondary tasks of buoy laying and lighthouse supply, might be used in its primary function for most of the year.

The first large icebreaker to be built in this period was the d’Iberville, completed in 1952. Reflecting much improvement in hull from and size over the old pre-war icebreakers she was, even then, something of a reversion to type in her machinery which is steam reciprocating, albeit of an improved type known as the Unaflow engine. Hailed at the time, at least officially, as being preeminent among the icebreakers of the western hemisphere, it was her tonnage and power which entitled her to this position, for she was already outclassed in other ways.

Icebreakers must be able to work in isolation for long periods, owing to the danger of becoming fast in the ice, and they must also have the maximum possible radius of action. Although the diesel engine has largely replaced steam in merchant shipping, the direct coupled diesel is unsuitable for working in ice, and the various types of geared machinery cannot withstand the shock of striking ice with the propeller. For these reasons electrical drive, coupled to a diesel or steam prime mover, is generally favoured for modern icebreakers.

In 1953, the diesel electric icebreaker Labrador was built at Sorel for the Royal Canadian Navy. Although completed within a year of the d’Iberville she was technically in advance, having diesel electric machinery controlled from the navigating bridge. The Labrador is generally similar in design to the Wind class icebreakers of the United States Navy. This type was originally fitted with bow propellers to assist in backing off the ice after impact and in washing away the broken pieces when in forward motion. This arrangement is not favoured in Canadian icebreakers owing to the virtual certainty of damage to the propellers under polar conditions.

When the Department of National Defence decided to withdraw from naval patrol of the Arctic, HMCS Labrador was paid off and transferred to the control of the Department of Transport in 1958. With her first rate capability and extended endurance she was a welcome addition to the fleet of Arctic icebreakers but the arrangement of decks and bulkheads, built to naval standards of watertight sub-division, leaves little room for cargo and her supply role is therefore limited.

The next step in the development of large icebreakers came in 1960 when the CCGS John A. Macdonald was completed at Lauzon, Que. A considerably bigger and more powerful ship than the Labrador, the Macdonald is an ocean-going icebreaker able to meet the most rigorous polar conditions. Her diesel-electric machinery of 15,000 horsepower is arranged in three units transmitting power equally to each of three shafts. Triple screws are now usual in the largest type of icebreaker, as they provide greater operational reliability and more efficient steering. The Macdonald has a range of 20,000 miles at ten knots and can carry stores and provisions sufficient to enable a full Arctic season to be spent without replenishment.

The capabilities of both vessels were demonstrated within a short time of entering service. In 1962 the Macdonald penetrated to the head of Tanqueray Fiord when, under the command of Captain J. C. Cuthbert, she had taken supplies to Eureka in company with the d’Iberville. Two years later, in September 1964, Captain N. V. Clarke took the Labrador up Kennedy Channel, between Ellesmere Island and Greenland, to reach the most northerly position ever attained by any Canadian ship. This position, in 81 deg. 45 min. North latitude, is only 60 miles from Alert which, it will be recalled, was named after the ship which had carried Nares to 82 deg. North in 1875. Considering that even a ship like the Macdonald runs some risk of becoming fast in these latitudes, and that the highest degree of judgement and skill is required in navigation there, it is remarkable that a wooden sailing ship with a compound engine of 60 nominal horsepower was able to reach Alert. The old explores required tremendous courage in the face of risks, and some luck; if it was unique that the underpowered Alert could get so far north, it was miraculous that she was able to return.

Aptly enough, as these lines were being written, the Macdonald was concerned in an incident which emphasizes the vulnerability of icebreakers in high latitudes. This narrative is as follows.

The USCG Northwind, an icebreaker of somewhat similar type to the Labrador, lost a propeller blade while working in heavy ice some 500 miles north of Point Barrow, a headland of the western Arctic on the shores of the Beaufort Sea. In this remote area, in September 1967, the Northwind was beset and in grave danger of becoming fast in the ice for the winter. Upon receipt of a call for assistance, the CCGS John A. Macdonald, under the command of Captain Paul M. Fournier, which had already traversed the Northwest Passage from the eastern Arctic to help the CCGS Camsell in support of supply ships in Mackenzie Bay, proceeded at best speed for the Chukchee Sea. She was one of the very few ships in the world which could have rendered assistance.

This episode, which brought honour to the ship in a commendation from the Commandant of the United States Coast Guard, is best described in the words of his citation:

“. . . the Macdonald, with another (U.S.) Coast Guard vessel, and as lead icebreaker, entered the icepack bound for Northwind. Despite increasingly severe ice conditions, shifting floes, changing winds, and the great risk presented by seemingly impenetrable pressure ridges which severely taxed the limits of both vessel and crew, Macdonald persevered and rendezvous was accomplished at 78 deg. 40 min. North. 168 deg. 06 min. West. The operation required the utmost in ice seamanship, skilful manoeuvring of the vessel and outstanding teamwork from the entire crew of the Macdonald which resulted in Northwind clearing the ice on 8 October. The courageous action, initiative, diligence and perseverance of the personnel on board the Macdonald during this hazardous operation were in keeping with the finest traditions of the United States Coast Guard.”

For a change of scene, the Macdonald returned to her base of Halifax by way of Victoria and the Panama Canal.

The main development has been one of size and power; other things being equal, a big icebreaker is better than a little one. From this point of view the d’Iberville, Labrador and John A. Macdonald are the capital ships of the Canadian Coast Guard, engaged in a continuous icebreaking task according to season. The potential of the group will be greatly increased with the completion of the CCGS Louis S. St. Lawrence in 1968, a vessel which will be the most powerful non-nuclear icebreaker in the world.

Virtually, all seagoing ships used by the Department in Canadian waters are designed to operate in ice to some extent. Half way between the two extremes of polar icebreaker and ice strengthened lighthouse and buoy tender, a group of middle-sized icebreakers, all modern ships, can handle all but the most arduous tasks according to size. These are the Camsell, which services the lights and buoys of the Pacific coast in winter and the western Arctic supply in summer, the Wolfe, the Sir Humphrey Gilbert and the second Montcalm. In a class by itself the icebreaking cable layer John Cabot, the only ship of its kind in existence, is operated under the Department in conjunction with the Canadian Overseas Tele-communication Corporation.