The next time you go to the beach and pick up a piece up something from the sand, think of the story of how it arrived there. Is it something lost from the local town, or something that has drifted for years to arrive here just for you?

Early in the 1900’s – commercial Japanese crab fishermen began replacing wooden and cork floats on their fishing nets with free blown glass floats. When the nets broke loose or were lost, the net rotted and the glass balls floated free from their nets and drifted across the Pacific, along with much other debris, on the Kuroshio Current (also known as the Black Stream or Japanese Current). This is a north-flowing ocean current on the west side of the North Pacific Ocean and it is part of the North Pacific ocean gyre1.

1910 – PRESENT – Every year the Kuroshio Current brings material from Asia to North American shores – floats, shoes, boats, wood, bottles, cans, etc. – garbage!

March 11, 2011 – a powerful, magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit northeastern Japan, triggering a tsunami with 10-meter-high waves that reached the U.S. West Coast. So much debris was washed out to sea from Japan that forecasters have said that because of prevailing ocean currents (see above), the garbage will wash up on North American coastlines by 2014.

March 11, 2011 – a powerful, magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit northeastern Japan, triggering a tsunami with 10-meter-high waves that reached the U.S. West Coast. So much debris was washed out to sea from Japan that forecasters have said that because of prevailing ocean currents (see above), the garbage will wash up on North American coastlines by 2014.

November 11, 2011 – Is Tsunami debris from Japan reaching BC? Beachcombers in BC on the west coast of Vancouver Island have been finding plastic drink bottles imprinted with Asian writing, floats, wood, and other debris. Is this from the the Japanese Tsunami? Not likely! See the video and the news story which is raising the alarm in the link above.

It takes approximately seven (7) years for debris from Japan to reach western American shores, and some of it floats longer.2 From the oceanographer’s reports, the acres of garbage is coming faster for some reason. Maybe because of the greater volume, and hence greater exposure to the wind. Debris moves faster if it is exposed to the wind. It is estimated at 20 million tonnes and covering an area the size of the state of California. The main part of the debris field is not expected until about 2014.

Please take a look at the following video which shows people beachcombing for glass balls (Asian fishnet floats). Look at all the garbage on the beaches, washed ashore by the winds, with help from the currents mentioned above. Lots of Asian material on the beaches there too (2010).

[media url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YtyUiHXeFlI” width=”400″ height=”300″]

When the debris from the Japanese Tsunami hits our shores, we will know it!

February 12, 2013 – Millions of tonnes of tsunami debris approaching B.C.’s coastal communities

Tonnes of Japanese tsunami debris are expected to wash up along Pacific shores starting in earnest this year, and B.C.’s coastal communities are bracing for a barrage of garbage on their beaches.

[private]“This is a huge issue,” said Ucluelet Mayor Bill Irving in advance of a Tuesday night public meeting.

“Our number 1 concern is getting plastics out of the system as quick as possible so that they don’t affect the environment,” Irving said, adding the impact on locals and tourism were also at issue.

“We don’t want to see our beaches covered in garbage,” he said.

At the moment, he added, “I don’t think you can travel a metre without seeing at least three or four pieces of plastic or rope or bottle.”

WORSE EXPECTED IN SPRING

And this spring the debris is expected to get worse.

The March 11, 2011 magnitude 9.0 earthquake and tsunami in Japan killed more than 21,000 people, triggered a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, and sent tonnes of debris spilling into the ocean.

Just how much debris is swirling in the sea is hotly debated.

Scientists at the University of Hawaii have estimated the amount at more than 18 million tonnes. Other estimates are as high as 25 million tonnes. Yet the Japanese Ministry of the Environment says just five million tonnes washed out to sea.

The majority of the debris is expected to sink or to end up caught in the eddies of the North Pacific garbage patch.

OCEAN OF GARBAGE

But that could still leave millions of tonnes afloat at sea — recent estimates put the number at 1.5 to 3 million tonnes. That represents an ocean of garbage some experts think could be the size of California — and the bulk of this is expected to hit the Pacific Coast, from California to Alaska — in 2013-14.

Irving said the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has warned coastal B.C. communities to expect the first big increase in debris in April.

“Right now it has levelled off, but they think it is really going to show up in April. They see quite large volumes arriving,” Irving said.

Some debris has already hit shores all along the Pacific coast, and everything from lumber to motorcycles has washed up on B.C. beaches.

SMALL ITEMS

Small items, mostly plastic bottles and personal items, were seen in December 2011. Larger items, like shipping drums, began to arrive last May.

In the spring of 2012, the largest flotsam to date — a derelict Japanese fishing vessel — drifted within a few hundred kilometres of our coast before the U.S. Coast Guard sank it as a safety hazard.

A September 2012 update from a Fisheries and Oceans official stated the government “expect heavier amounts to arrive in the spring of 2013” in B.C.

MONITORING INFLUX

Karla Robison, Ucluelet’s manager of environmental and emergency services and a provincial and regional tsunami committee member, said she has been monitoring incoming debris at for months now to try to gauge the flow.

Robison said she’s seen estimates of eventual debris accumulation from a half-tonne per mile of coastline to up to 131 tonnes per mile. And some models indicate the Northwest Coast could see more of the larger items pushed ashore.

But, she cautioned, “it’s really hard to predict. It’s a huge ocean, and a lot of it sunk.”

In Ucluelet in November, she said, “There were so many pieces of Styrofoam and plastic bottles it was overwhelming. And then it dropped off again. I’m thinking it’s almost the calm before the storm.”

PUBLIC MEETING

Robison is holding a public meeting at Tofino’s Botanical Gardens Tuesday at 7 p.m. She is also recruiting volunteers to help with the shoreline cleanup efforts, which are expected to peak this summer.

Tofino’s mayor, Josie Osborne, said the city’s key concerns “are that we are able to deal with debris promptly, and able to remove it in an environmentally responsible and safe way, taking care of those items that might be traceable back to someone in Japan.”

Osborne said Tofino is anticipating a co-ordinated approach with its neighbours — the District of Ucluelet, the Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District, Parks Canada, First Nations — and leadership from the provincial and federal governments.

SMALL IS CHALLENGING

“The most challenging debris are the smallest pieces,” Osborne said.

“We will be able to deal with large objects, one way or another, but I’m very concerned about the possible amount of tiny styrofoam and plastic pieces that may be washing ashore for years to come.

“It’s challenging to distinguish the source of debris on local beaches, whether it is from the Japan tsunami or from a fishing vessel or some other source.

“We are beginning to see debris that I am quite confident is from the tsunami, like plastic bottles and containers.

“Last week I found a toy ball with Japanese characters on it. It was a startling find. Usually when I find pieces of debris I ask myself several times, ‘Is this really from the Japan tsunami?’— but finding this ball with Japanese writing really made it sink in.”

DEBRIS BINS SET UP

As part of their preparations, Ucluelet set up dedicated tsunami debris bins at the local public works yard. Ultimately, much of the plastic, glass, wood and other reusable materials are expected to be recycled, the rest disposed of.

But Irving said the regional government is still trying to get provincial funding for recycling and debris transportation.

The debris also presents an administrative hazard: While items washing ashore are the responsibility of local governments, offshore debris falls to federal agencies to deal with, and debris between low and high tide markers in the intertidal zone is in the province’s jurisdiction.

3 LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT

In B.C., this means involvement from agencies such as the Ministry of Environment, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, the Integrated Land Management Bureau, and the Emergency Management Agency, as well as local governments.

The province struck a Tsunami Debris Co-ordinating Committee last January, with federal, provincial and local officials, to organize its response. The group is also collaborating with NOAA and coastal American states, plus Hawaii.

According to the committee, the amount of debris that B.C. eventually sees on its shores could be less than expected — perhaps a third of the total floating mass.

“The other two-thirds (of non-sinking material) will go back toward Hawaii or end up in the North Pacific [garbage] convergence zone,” the committee stated.

RADIOACTIVITY UNLIKELY

The group also played down fears that some of the debris could be contaminated with radioactivity from Fukishima, noting that “the majority of the debris will have been swept away from Japan during and immediately following the earthquake and tsunami – prior to the issues with the nuclear reactor.”

Despite this, the province will do some sample testing of debris as a safeguard. To date, no test has detected radiation, according to the September 2012 update from DFO.

The committee also stated that the possibility of human remains washing up was “highly unlikely.”

TOFINO ISSUES WARNING

Tofino city officials have warned residents and tourists not to collect the debris as souvenirs.

Anyone who comes across any potentially polluting or hazardous debris such as leaking oil drums and other waste should contact the Provincial Emergency Co-ordination Centre at 1-800-663-3456.

Residents of Ucluelet who come across tsunami debris can contact: emergency@ucluelet.ca ” TARGET=”_blank”>emergency@ucluelet.ca or call 250-726-7744.

The tsunami committee advises B.C. residents who find easily identifiable items to report them to the NOAA via email at: DisasterDebris@noaa.gov.

To learn more about B.C.’s debris cleanup plan, visit: TsunamiDebrisBC.ca.

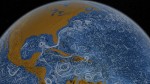

October 13, 2012 – Perpetual Ocean

October 13, 2012 – Perpetual Ocean

This visualization shows ocean surface currents around the world during the period from June 2005 through December 2007. The visualization does not include a narration or annotations; the goal was to use ocean flow data to create a simple, visceral experience.

This visualization was produced using model output from the joint MIT/JPL project: Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean, Phase II or ECCO2. ECCO2 uses the MIT general circulation model (MITgcm) to synthesize satellite and in-situ data of the global ocean and sea-ice at resolutions that begin to resolve ocean eddies and other narrow current systems, which transport heat and carbon in the oceans. ECCO2 provides ocean flows at all depths, but only surface flows are used in this visualization. The dark patterns under the ocean represent the undersea bathymetry. Topographic land exaggeration is 20x and bathymetric exaggeration is 40x.

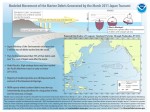

August 14, 2012 – How wind-blown Japanese tsunami debris may move across the Pacific

This animation shows how wind affects the rate at which debris from the Japanese tsunami moves across the Pacific. It is a mathematical model that incorporates a great deal of ocean data, like ocean current and wind speed, but is not a direct measurement of actual debris pieces.

August 06, 2012 – Dust particles from Asia pollute US air with interesting video.

New analysis of NASA satellite information shows 64-million tons of dust, pollution and other nasty little particles, with potential to affect both us and our climate, survive a trip all the way across the ocean and arrive safely in North America each year. Even worse, models show Asia is the primary source of this nasty stuff.

July 30, 2012 – Marine Debris Information from NOAA Excellent site giving up-to-date information on what is happening with the tsunami debris.

July 27, 2012 – Gary Griggs. Our Ocean Backyard: Invasion from the sea

July 26, 2012 – Dateline: Debris

. . . the jurisdiction scheduled to absorb the majority, B.C., with its labyrinthine 965 km-long coast (243,000 km total shoreline including islands), has no plans in place, no monies set aside, no idea what to do, and, until about two weeks ago, no one even studying the problem. “It’s so hypothetical at this point,” Environment Minister Terry Lake inexplicably stated last month.

July 24, 2012 – Tsunami debris widens Pacific Garbage Patch

Researchers making their first trip through the so-called Giant Pacific Garbage Patch since the 2011 Japan tsunami have concluded that plastic debris from the tragic event is making the patch bigger than ever.

They say it is now 2,000 miles wide.

“The entire North Pacific Gyre is now one giant accumulation zone of plastic pollution,” said expedition leader Marcus Eriksen in a press release. Large objects the researchers have found include half of a Japanese fishing boat and a fully-inflated tire.

July 19, 2012 – Debris from Japan’s Tsunami: Some Helpful Info Courtesy of NOAA

July 18, 2012 – Pacific Lost and Found: Tsunami Debris Project curated online

July 16, 2012 – B.C. Minister of Environment visits Haida Gwaii to see Japanese tsunami debris first hand

July 13, 2012 – All aboard the garbage cruise: Adventurers who sail through tons of trash from Japan tsunami (all in the name of research)

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2171900/Japan-tsunami-Astonishing-satellite-image-shows-1-5million-tonnes-debris-swept-US.html#ixzz20VgnDBLO

July 10, 2012 – The Garbage Cruise – A Sea of Floating Tsunami Debris Tsunami debris aside, the Pacific Ocean “is one giant garbage patch”, according to Eriksen.

July 09, 2012 – B.C. forms task force for tsunami debris cleanup Environment minister tours Haida Gwaii but says ‘premature’ to earmark cleanup funds

July 03, 2012 – Japanese boat in Southeast Alaska may be tsunami debris

July 03, 2012 – Tsunami debris surveys underway but will cleanup funding arrive in time? Today the Marine Conservation Alliance Foundation (MCAF) released the results of their tsunami debris monitoring program. Further monitoring efforts are underway but additional funding is necessary to conduct cleanup activities.

July 02, 2012 – NOAA survey done Jeep Rice of NOAA’s Auke Bay Lab said the survey project started about 40 years ago, with surveys every five years or so.

June 30, 2012 – Fishermen, Oregon officials discuss dangers of tsunami debris at sea Commercial fisherman Mark Schneider said he watched a refrigerator float past his boat, Sea Princess, while he and his crew were salmon fishing on Thursday near Newport.

June 30, 2012 – Fishermen, Oregon officials discuss dangers of tsunami debris at sea – Have you ever run into a refridgerator at high speed on the open sea? Tsunami debris may pose such hazards. What else is coming?

June 25, 2012 – Tracking Japan’s Tsunami Debris (Infographic)

June 24, 2012 – NOAA Scientists Complete First Phase of Alaska Marine Debris Survey NOAA’s Marine Debris Program provided funding for the survey, which wrapped up June 24 in Juneau. The NOAA Marine Debris Program asks that members of the public visit their website on the Japanese tsunami marine debris –http://marinedebris.noaa.gov/tsunamidebris/ – to learn about procedures when they encounter marine debris. If one finds tsunami debris, NOAA asks that it be reported to: DisasterDebris@noaa.gov.

June 24, 2012 – NOAA Scientists Complete First Phase of Alaska Marine Debris Survey NOAA’s Marine Debris Program provided funding for the survey, which wrapped up June 24 in Juneau. The NOAA Marine Debris Program asks that members of the public visit their website on the Japanese tsunami marine debris –http://marinedebris.noaa.gov/tsunamidebris/ – to learn about procedures when they encounter marine debris. If one finds tsunami debris, NOAA asks that it be reported to: DisasterDebris@noaa.gov.

June 23, 2012 – B.C. is wait-and-see over tsunami debris Province cautious while Americans devote funding to Japanese wreckage recovery effort

June 22, 2012 – Tsunami debris turning B.C. beaches into ‘landfills’ Styrofoam, propane tanks, barrels, and gas cans littering Haida Gwaii beaches

June 19, 2012 – Consulate: Japanese owner of tsunami-lost boat that washed up in Wash. doesn’t want it back

June 18, 2012 – Scientists Kick-Off First NOAA-LED Survey of Southeast Alaska Beaches for Tsunami Debris

June 17, 2012 – Tsunami debris appears to avoid Midway

“Everyone in the oceanic administrations and the mariners at sea are eager to know where that debris from the tsunami has moved,” said Robyn Thorson, the regional director for U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

June 13, 2012 – FedEx Returns Long-lost Possessions Washed to Sea by Japanese Tsunami

June 09, 2012 – As Japan debris washes up in the US, scientists fear break in natural order

June 09, 2012 – Japan Tsunami Debris: Under Control or on the Brink of Disaster?

June 07, 2012 – 100 Tons of ‘Alien’ Sea Life Wash Up With Tsunami Dock (now this is interesting!)

June 06, 2012 – Tsunami debris: Huge dock washes up on Oregon coast

June 05, 2012 – Inspection reveals B.C. beaches a global garbage dump A global garbage dump – not all from the tsunami!

June 05, 2012 – University of Washington researchers warn tsunami debris not the biggest ocean mess

June 05, 2012 – Follow the Sea Dragon

. . . a team of scientists has set sail aboard the Sea Dragon to get a close-up look at the debris as it floats in the ocean. It’ll be the first physical accounting of the floating debris — up ‘til now, scientists have modeled the likely path of the debris based on past wind and ocean current patterns.

Follow the blog on the National Geographic website.

June 01, 2012 – Tsunami debris? Go online to find out how to deal with it safely Hmmm, this is a big help tsunamidebris.ca has links to other sites including American ones. Does the British Columbia government think that the Americans will help clean up our beaches? Think again!

Another misleading story on the same theme: Website helps prepare for tsunami debris Wow! That was a big help second time around.

May 30, 2012 – A Tsunami of Exaggeration (this is another article supporting my theory that 90% of the foreign garbage on the beaches is normal debris that occurs each year – most people have never ever heard about it or seen it mentioned until the tsunami happened!)

May 27, 2012 – The great Pacific garbage reality (this is a great article backing up what I have been saying – most of the debris is just the same garbage that accumulates every year on the Pacific coasts.

May 25, 2012 – Waiting for the next big wave

May 25, 2012 – Tsunami motorcycle heading to Harley museum

May 24, 2012 – 6.1 earthquake strikes northeastern Japan

May 23, 2012 – Photos: Japan tsunami debris reaches Alaska

May 23, 2012 – Oceanographer expects bones in tsunami debris

[/update]

[spoiler title=”More news here . . .”]

May 20, 2012 – Trash to the rescue (something a little different!)

May 20, 2012 – Alaska sightings of tsunami debris increasing, so what now?

May 18, 2012 –Spy satellites used in search for tsunami debris

May 19, 2012 – Tsunami debris clean-up plan urged

May 18, 2012 – U.S. not ready for Japan tsunami debris (+video)

May 17, 2012 – Tsunami debris on the way; scientists say not to worry

May 17, 2012 – Anyone who finds any tsunami debris can go to our webpage, BC Ministry of Environment, and can register the material. . .The Northern View

May 11, 2012 – Coastal B.C. frets over Japanese tsunami debris cleanup

May 11, 2012 – Volunteers sought for West Coast tsunami debris cleanup

May 10, 2012 – Do not treat tsunami debris like souvenirs: Tofino mayor What are going to do? Return empty shampoo bottles? Get realistic! There are 1.5 million tons of the stuff coming!

May 10, 2012 – Tsunami garbage piling up on West Coast beaches

May 01, 2012 – Tsunami motorcycle owner located in Japan

April 30, 2012 – Tons of Suspected Japan Tsunami Debris Wash Ashore in Alaska

April 29, 2012 – Motorcycle washed up in B.C. may be Japanese tsunami debris

April 23, 2012 – Picking up the pieces after Japan’s tsunami, giving ‘garbage’ new meaning in Tofino

But Japan’s deputy consul general in Vancouver, Kinji Shinoda, remains cautious about tying the debris to the tsunami, saying tonnes of debris has sunk, and Canadians and even some major media outlets have already misidentified the Chinese characters on some garbage as Japanese.

April 23, 2012 – Boy’s football lost in tsunami found in Alaska

April 06, 2012 – US Coast Guard sinks tsunami ‘ghost ship (BBC) (+video) – Finally, that is over! Next?

April 05, 2012 – Japanese ‘ghost ship’ on fire and listing off Alaska (+video)

April 04, 2012 – Japanese tsunami ‘ghost ship’ off B.C. to be sunk (with video)

April 02, 2012 – Drifting tsunami ship turns north toward Alaska

March 23, 2012 – Tsunami-linked fishing boat adrift off B.C.

February 23, 2011 – Path of Tsunami debris mapped out

January 08, 2012 – Beach discoveries fuel concern over arrival of Japanese tsunami debris

December 28, 2011 – More Japanese Debris Found on Island [/spoiler]

[media url=”https://ccanadaht3.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Debris-Field.flv” width=”400″ height=”350″]

Above is an animation of how the Japanese tsunami debris field has spread since March 2011. Courtesy of the International Pacific Research Center.

*****************************

FOOTNOTES:

1 A gyre in oceanography is any large system of rotating ocean currents, particularly those involved with large wind movements. Gyres are caused by the Coriolis Effect; planetary vorticity along with horizontal and vertical friction, which determine the circulation patterns from the wind curl. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ocean_gyre. A good description of the offending gyre is found here.

[private]

Source: http://metronews.ca/news/canada/239477/does-japan-tsunami-debris-threaten-ocean-life/

Paul Hill, an oceanographer at Dalhousie University in Halifax, says currents are the reason tsunami debris has been coming to North America.

There are five major gyres — large spinning currents — in the world’s main ocean basins.

On the western side of ocean basins, gyres flow from the Equator to higher latitudes, says Hill.

“Those currents are particularly strong on the western margins of ocean basins. Once they get up to about the latitudes of the border between Canada and the U.S. . . . they turn east. As they turn east they slow down but they continue to flow along,” he says.

When the currents get to the eastern margin of ocean basins — Canada’s West Coast — they turn southward and head back down toward the Equator, where they turn westward to complete the loop.

KURISHO CURRENT

The Pacific’s strong current on the western side of the ocean is called the Kurisho current. Its equivalent in the Atlantic is the Gulf Stream.

“Those currents flow along as fast as you can walk in some places. . . five kilometres per hour,” says Hill, explaining the currents are relatively narrow but transport huge amounts of water.

“That current sweeps by Japan and when all the debris washed out to sea as the waters from the tsunami flowed back off the land it got caught up in the Kurisho.”

The Kurisho around Japan turns eastward and flows across the ocean. It then slows down to about a rate of half a kilometre per hour, says Hill.

At that speed it takes just over a year to get across the Pacific — roughly 7,500 kilometres.

Not all the debris will end up on the shoreline, some of it will float southward, along the U.S. coast. Some debris will also float back westward across the ocean, predicts Hill.

“Some gets beached and we see that, and there’s other stuff out there that we don’t see because most of us aren’t out there,” Hill says.

GARBAGE PATCH

The large garbage patch in the middle of the North Pacific Ocean is such an example. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch — roughly the size of Texas, say some experts — is in the middle of the gyre. Some of the buoyant items get pushed into the centre, staying there until they naturally degrade or sink, Hill says.

Debris can attract marine life, offering a place of refuge for small fish to hide from predators. However, the concerns lie with toxic materials.

The problem is twofold — toxins can leach out of plastics and marine organisms can consume plastics and choke on them, says Hill.

[/private]

2 Today most of the glass floats remaining in the ocean are stuck in a circular pattern of ocean currents in the North Pacific. Off the east coast of Taiwan, the Kuroshio Current starts as a northern branch of the western-flowing North Equatorial Current. It flows past Japan and meets the arctic waters of the Oyashio Current. At this junction, the North Pacific Current (or Drift) is formed which travels east across Pacific before slowing down in the Gulf of Alaska. As it turns south, the California Current pushes the water into the North Equatorial Current once again, and the cycle continues. Much garbage is still drifting on these ocean currents, impolitely known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Occasionally storms or certain tidal conditions will break some garbage from this circular pattern and bring it ashore on the beaches of Alaska, British Columbia or Washington and Oregon. It is estimated that glass floats for example must be a minimum of 7–10 years old before washing up on beaches in Alaska. Most floats that wash up, however, would have been afloat for 10 years. A small amount of garbage is also trapped in the Arctic ice pack where there is movement over the North Pole and into the Atlantic Ocean. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glass_float

*********************************

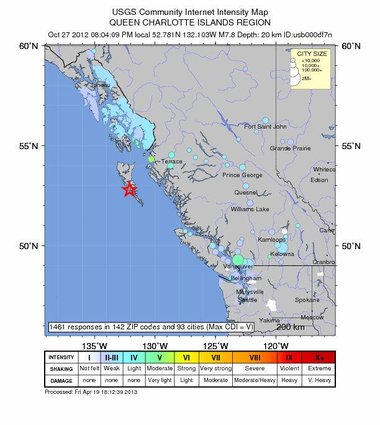

May 04, 2013 – Fishing float rides 2 tsunamis — and survives

A fishing float thought to be Japan tsunami debris was carried into a Canadian forest by a 2012 tsunami after the Haida Gwaii earthquake.

By Becky Oskin

A barrel-size black plastic float torn loose by the 2011 Japan tsunami may have been tossed into a Canadian forest by a second tsunami in 2012, researchers say.

[private]

Though the hollow float hasn’t been officially confirmed as tsunami debris, it is identical to a float embossed with the name “Musashi” found in the U.S. Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge in May 2012, the researchers said. A similar float was traced to an oyster farm in northeast Japan. The debris from the devastating 2011 tsunami has washed up from Alaska to California to Hawaii.

“This is a float that was caught up in the tsunami from Japan, so it is doubly tsunami debris,” seismologist Alison Bird of the Geological Survey of Canada said at the Seismological Society of America’s annual meeting on April 19. The float was discovered in Sunday Inlet on Moresby Island in British Columbia. The island is part of Haida Gwaii, once called the Queen Charlotte Islands. [Infographic: Tracking Japan’s Tsunami Debris]

Second tsunami

The magnitude-7.7 Haida Gwaii earthquake on Oct. 27, 2012, triggered the tsunami, which raced far up western inlets on Moresby Island and Graham Island, but caused little damage on either island’s populated eastern side. The powerful wave also sped straight to Hawaii, hitting with a maximum height of 2.5 feet (76 centimeters) and no serious flooding or damage.

The tsunami run-up, which measures how far water surges onshore, was as much as 22 feet (7 meters) in protected bays on the islands’ west coasts, Gary Rogers, a Geological Survey of Canada scientist, said at the meeting. (A hurricane-force storm hit the islands just after the earthquake, destroying any record of the tsunami except in protected areas, Rogers said.)

Seaweed wrapped around trees in Sunday Inlet on Moresby Island by the 2012 Haida Gwaii tsunami.

Lucinda Leonard, the Geological Survey scientist who discovered the fishing float, also found dead fish in the forest moss and logs shoved out of place by the tsunami. Seaweed was wrapped around tree branches up to 8 feet (2.5 m) high in Sunday Inlet, where the float ended its journey.

A strange earthquake

Geologists are still puzzling over the unusual Haida Gwaii earthquake, which surprised scientists because of its unexpected style. Understanding what caused the quake will help them forecast the region’s earthquake and tsunami hazards.

Two tectonic plates meet west of Haida Gwaii: the Pacific plate and the North America plate. A strikingly obvious strike-slip fault, the Queen Charlotte fault, has been thought to mark the boundary between the two plates. Strike-slip faults are mostly vertical fractures where two blocks of Earth’s crust slide past each other horizontally. The Queen Charlotte unleashed Canada’s largest recorded temblors, in 1949, a magnitude 8.1.

But the 2012 earthquake was a thrust earthquake, on a previously unknown fault west of the Queen Charlotte fault. The thrust fault hides under a giant pile of sediments. In a thrust quake, two blocks of crust move toward each other, like in subduction zones.

The location of the 2012 Haida Gwaii earthquake, a magnitude 7.7.

The location of the 2012 Haida Gwaii earthquake, a magnitude 7.7.

Rethinking the plate boundary

Given the region’s ancient tectonic history, there could be a remnant piece of oceanic crust sliding down beneath the southern part of Haida Gwaii, Rogers said. There is some evidence for this from seismic waves, which change their speed when they pass through old, cold crust sitting in hotter mantle rocks. (Earth’s mantle lies beneath the crust.)

“It all looks very much like a subduction zone, given the down-bowing of oceanic crust and the accretionary prism (of sediments),” Rogers said. The Pacific plate could be subducting under Haida Gwaii, and thus the North American plate, as far north as the middle of Moresby Island, he said.

Now, scientists want to figure out if the plate boundary is strike-slip or subduction, or a combination of both. They also want to know if there could be bigger earthquakes, and what happens to the Queen Charlotte strike-slip fault when it meets this mysterious new fault. [7 Ways the Earth Changes in the Blink of an Eye]

“If this is some sort of remnant subduction, are we always going to get a small amount of strike-slip with more thrust events?” David Oglesby, a seismologist at the University of California, Riverside, asked at the meeting. “It does raise the possibility that you could get significant slip down there.”

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+.Original article on LiveScience’s OurAmazingPlanet.

- Photos: Tsunami Debris & Trash on Hawaii’s Beaches

- Waves of Destruction: History’s Biggest Tsunamis

- The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.[/private]

******************************

Japan Earthquake & Tsunami of 2011: Facts and Information

by Becky Oskin, Our Amazing Planet Staff Writer August 22, 2013

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude-9 earthquake shook northeastern Japan, unleashing a savage tsunami.

The effects of the great earthquake were felt around the world, from Norway’s fjords to Antarctica’s ice sheet. Tsunami debris continues to wash up on North American beaches two years later.

Japan still recovering

In Japan, residents are still recovering from the disaster. Radioactive water was recently discovered leaking from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which suffered a level 7 nuclear meltdown after the tsunami. Japan relies on nuclear power, and many of the country’s nuclear reactors remain closed because of stricter seismic safety standards since the earthquake. Two years after the quake, about 300,000 people who lost their homes were still living in temporary housing, the Japanese government said.

Earthquake a surprise

The unexpected disaster was neither the largest nor deadliest earthquake and tsunami to strike this century. That record goes to the 2004 Banda-Aceh earthquake and tsunami in Sumatra, a magnitude-9.1, which killed more than 230,000 people. But Japan’s one-two punch proved especially devastating for the earthquake-savvy country, because few scientists had predicted the country would experience such a large earthquake and tsunami. . . . more

[private] Japan’s scientists had predicted a smaller earthquake would strike the northern region of Honshu, the country’s main island. Nor did they expect such a large tsunami. But there had been hints of the disaster to come. The areas flooded in 2011 closely matched those of a tsunami that hit Sendai in 869. In the decade before the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, a handful of Japanese geologists had begun to recognize that a large earthquake and tsunami had struck the northern Honshu region in 869. However, their warnings went unheeded by officials responsible for the country’s earthquake hazard assessments. Now, tsunami experts from around the world have been asked to assess the history of past tsunamis in Japan, to better predict the country’s future earthquake risk.

The cause

The 2011 Tohoku earthquake struck offshore of Japan, along a subduction zone where two of Earth’s tectonic plates collide. In a subduction zone, one plate slides beneath another into the mantle, the hotter layer beneath the crust. The great plates stick and slip, causing earthquakes. East of Japan, the Pacific plate dives beneath the overriding Eurasian plate. The temblor completely released centuries of built up stress between the two tectonic plates, a recent study found.

The earthquake started on a Friday at 2:46 p.m. local time (5:46 a.m. UTC). It was centered on the seafloor 45 miles (72 kilometers) east of Tohoku, at a depth of 20 miles (32 km) below the surface. The shaking lasted about six minutes. [Infographic: How Japan’s 2011 Earthquake Happened]

Early warning

Residents of Tokyo received a minute of warning before the strong shaking hit the city, thanks to Japan’s earthquake early warning system. The country’s stringent seismic building codes and early warning system prevented many deaths from the earthquake, by stopping high-speed trains and factory assembly lines. People in Japan also received texted alerts of the earthquake warning on their cellphones.

Deaths

More than 18,000 people were killed in the disaster. Most died by drowning.

Less than an hour after the earthquake, the first of many tsunami waves hit Japan’s coastline. The tsunami waves reached run-up heights (how far the wave surges inland above sea level) of up to 128 feet (39 meters) at Miyako city and traveled inland as far as 6 miles (10 km) in Sendai. The tsunami flooded an estimated area of approximately 217 square miles (561 square kilometers) in Japan.

The waves overtopped and destroyed protective tsunami seawalls at several locations. The massive surge destroyed three-story buildings where people had gathered for safety. Near Oarai, the tsunami generated a huge whirlpool offshore, captured on video.

Nuclear meltdown

The tsunami caused a cooling system failure at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which resulted in a level 7 nuclear meltdown and release of radioactive materials. About 300 tons of radioactive water continues to leak from the plant every day into the Pacific Ocean, affecting fish and other marine life.

The response

In the tsunami’s aftermath, Japan’s Meteorological Agency was criticized for issuing an initial tsunami warning that underestimated the size of the wave. The country recently unveiled a newly installed, upgraded tsunami warning system. In some regions, such as Miyagi and Fukushima, only 58 percent of people headed for higher ground immediately after the earthquake, according to a government study. Many people also underestimated their personal risk, or assumed the tsunami would be as small as ones they had previously experienced, the study found.

Scientists from around the world descended on Japan following the earthquake and tsunami. Researchers sailed offshore and dropped sensors along the fault line to measure the forces that caused the earthquake. Teams studied the tsunami deposits to better understand ancient sediment records of the deadly waves. Earthquake engineers examined the damage, looking for ways to build buildings more resistant to quakes and tsunamis. Studies are ongoing today.

Worldwide effects

The tsunami waves also traveled across the Pacific, reaching Alaska, Hawaii and Chile. In Chile, some 11,000 miles (17,000 km) distant, the tsunami was 6.6 feet (2 meters) high when they reached the shore.

The surge of water carried tons of debris out to sea as it receded. Japanese docks and ships, and countless household items, have arrived on U.S. and Canadian shores in the ensuing years. The U.S. Coast Guard fired on and sank the derelict boat 164-foot Ryou-Un Maru in 2012 in the Gulf of Alaska. The ship started its journey in Hokkaido.

Amazing facts

Here are some of the amazing facts about the Japan earthquake and tsunami.

- The earthquake shifted Earth on its axis of rotation by redistributing mass, like putting a dent in a wobbling top. The temblor also shortened the length of day by about a microsecond.

- More than 1,000 aftershocks have hit Japan since the earthquake, the largest a magnitude 7.9.

- About 250 miles (400 km) of Japan’s northern Honshu coastline dropped by 2 feet (0.6 meters).

- The jolt moved Japan’s main island of Honshu eastward by 8 feet (2.4 meters).

- The Pacific Plate slid westward near the epicenter by 79 feet (24 m).

- In Antarctica, the seismic waves from the earthquake sped up the Whillans Ice Stream, jolting it by about 1.5 feet (0.5 meters).

- The tsunami broke icebergs off the Sulzberger Ice Shelf in Antarctica.

- As the tsunami crossed the Pacific Ocean, a 5-foot high (1.5 m) high wave killed more than 110,000 nesting seabirds at the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge.

- In Norway, water in some fjords pointing northeast toward Japan (up and over the pole) sloshed back and forth as seismic waves from the earthquake raced through.

- The earthquake produced a low-frequency rumble called infrasound, which traveled into space and was detected by the Goce satellite.[/private]

Nothing out of the ordinary here John. We would see fresh marine growth on anything that has been in the water since March…. small pelagic barnacles or fuzzy red algae. All of the Japanese junk on the beaches right now is clean and bare.

Hard to tell there is always garbage from Japan washing up. We found 7 individual flip flops from Japan last week.