Sentinels Encased in Ice by Elinor DeWire

from WeatherWise November-December 2011

The ice was here, the ice was there

The ice was all around;

I t cracked and growled, and roared and howled

Like noise in a swound…

—Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Caption: St. Joseph Pierhead in Michigan as it appeared on December 20, 2010.

In December 2010, images of Cleveland Harbor West Pierhead Lighthouse appeared on international news broadcasts, and a video of the lighthouse taken by a Cleveland, Ohio, news station went viral on YouTube. The fascination had nothing to do with the light’s solicitous mission of guiding shipping into the Cuyahoga River, nor did it reflect interest in the beacon’s 100th anniversary , just months away . The excitement was about ice, lots of

it, wondrously transforming the sentinel’s exterior into — in the words of a British news station — a “stunning ice palace.”

The public was mesmerized. Nature had created something magical just in time for the holidays. The massive arctic blast had descended on Lake Erie around December 9, churned the lake into a frigid soup, and produced powerful waves that slammed the pierhead. Hour-by-hour, layers of ice were laid down until the entire lighthouse was shrouded. Heavy lake-effect snow on December 13 and 14 heaped on more winter majesty .

Such icy spectacles are not uncommon. Icing-over of lighthouses occurs every year in northern climates, some years worse than others. In the modern era of high-tech navigation, an iced-over lighthouse is mostly a curiosity — a tourist attraction. Few mariners depend solely on lighthouses these days. Many have been phased out, and

those that remain operate with automatic devices that turn on and off the lights and fog signals. There are no resident lightkeepers employed to run them . Step back 50 years or more, however, and the story changes. As late as the 1970s, keepers still lived at lighthouses and had to endure all manner of weather calamities, including ice.

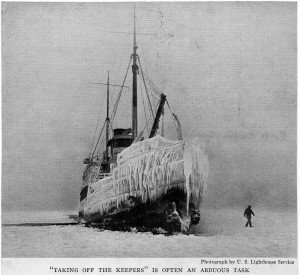

Caption: The USLHT Marigold was responsible for getting offshore lightkeepers safely delivered to the mainland before ice conditions made Lake Superior a frozen wasteland. While the Marigold normally finished up this duty by December 1, an early cold blast in 1919 complicated her mission. Here, she was pictured doing a little ice-breaking on her own as a crewman trekked over the ice to the crew of a lighthouse.

Caption: The USLHT Marigold was responsible for getting offshore lightkeepers safely delivered to the mainland before ice conditions made Lake Superior a frozen wasteland. While the Marigold normally finished up this duty by December 1, an early cold blast in 1919 complicated her mission. Here, she was pictured doing a little ice-breaking on her own as a crewman trekked over the ice to the crew of a lighthouse.

A Dangerous History

Before ice-breaking technology came into broad use in the 1920s, winter weather made ship travel dangerous in northern waters—too risky even to depend on a lighthouse. Shipping on the Great Lakes, Lake Champlain, and the St. Lawrence Seaway closed down on December 1 and resumed at the end of March. Lighthouse keepers in these regions shut off their lights or switched them to low-intensity , and then came ashore for the winter. But the closing and opening dates weren’t always reliable. An early winter blast of cold could seize up every thing. A late spring thaw might com pound problems.

Getting the keepers off their lighthouses before ice closed the sea lanes often was hazardous. A good example was the December 1919 cold snap that caused hardship for offshore lighthouse crews and for the tender Marigold, the vessel tasked with removing the lightkeepers from Lake Superior’s sentinels. Conditions were especially bad at the notorious “ice lights”—Stannard Rock, Isle Royale, Rock of Ages, Racine Reef, and Lansing Shoal — where frigid, wind-driven ice jams formed around the towers. The Marigold suffered miserably trying to reach these men and only avoided becoming icebound itself by staying in constant motion. Lightkeepers were forced to climb down icy

towers with ropes and make their way over the piled-up ice to a waiting surfboat that transferred them to the tender. Some could simply walk across the ice to the tender and get aboard using the ship’s derrick and a sling chair.

Stannard Rock Lighthouse

Stannard Rock Lighthouse in Lake Superior had a reputation for freezing up in winter. The 110-foot stone lighthouse was placed in service in 1 882 on a concrete caisson near a perilous reef off Keeweenaw Peninsula, 24 miles from the nearest land. As the nation’s most distant lighthouse from shore, lightkeepers dubbed it “The Loneliest Place in the World.” Only en were permitted to live there, due to the remoteness and difficulty getting

crews on and off the tower.

During the first winter of the lighthouse’s career, there were problems with ice. Dampness in the tower caused a thin rim e to form on the walls on the coldest days. Keepers sometimes awoke with frost on their beards and eyelashes, or blankets frozen to their metal bunks. As the end of the shipping season approached every November

and cold storms swept down from Canada, they were diligent about keeping the entry door to the lighthouse free of ice. The Lighthouse Service tender usually made its way to the rock around Thanksgiving, hoping to remove the men before conditions at the tower became too dangerous for a landing. In preparation for their departure, the keepers switched on a low intensity light.

By the end of March, the tender would make its way back to the lighthouse to return the crew and reinstate the beacon for the shipping season ahead. Plenty of pick axes and sledgehammers were on board, since the entry door almost always needed to be de-iced before it could be opened. In some y ears, ice removal took several days. In the spring of 1922 , the keepers returned to the lighthouse and found that the half-inch protective iron sheathing around the concrete pier was completely torn away . Heavy overhanging ice had ruptured and collapsed the metal.

The winter of 1929 is remembered as one of the most bitter, with cold air settling over Lake Superior early . On December 4, the tender Amaranth arrived at Stannard Rock Light to remove the lightkeepers. As the ship approached in the evening darkness, the beacon was barely discernible. Its peculiar greenish glow seemed feeble, With mounting concern, Amaranth slowed to a crawl and threw her searchlight on the sentinel. It was an incredible scene: The stone tower was totally sheathed in ice and glistened like a mammoth iceberg. Ice covered everything — the tower, the hoisting equipment, fuel tanks, foghorns, and the sturdy caisson on which the lighthouse perched. Long icicles hung from the lantern gallery like monster teeth. The lantern itself was wrapped entirely in an icy shroud, its light struggling to escape. But on the deck, the keepers were shouting and waving. They had managed to keep the exterior doors open with a steam hose. The reason the light was so feeble, they later told the skipper of the Amaranth, was that the intense cold and battering waves had caused the kerosene vapor apparatus to fail. They were forced to use the old-style wick lamp, which could barely shine through the thick ice.

Stannard Rock’s principal keeper later reported:

The weather during the latter part of November at Stannard Rock Lighthouse was the worst that I have ever experienced in my 30 years or more on the Great Lakes … snow squalls … very cold … spray went over the dome every minute and plate glass outside the lantern became one solid mass of ice.…Everything iced up from top of tower down to the water’s edge.

Caption: Grand Haven Lighthouse on Lake Michigan gets an annual shroud of ice.

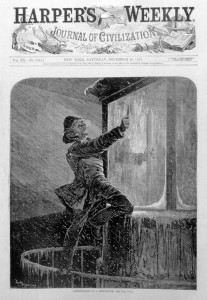

Caption: The December 1876 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine captured the lighthouse keepers’ annual travail with winter weather. Keeping the lantern windows clear of ice was a never-ending task in some regions.

Caption: Racine Reef (two images bottom) in Lake Superior and the Lansing Shoal Light in Lake Michigan were among about a dozen Great Lakes sentinels the U.S. Lighthouse Service dubbed “ The I ce Lights.” Winter weather usually encapsulated these structures in ice by New Year’s Day. Racine Reef Lighthouse served from 1906 until the early 1960s when it was demolished. The 1928 Lansing Shoal Light (top) is still on duty.

Caption: Michigan City East Pierhead Lighthouse, on the Indiana shore of Lake Michigan was photographed by the Lighthouse Service on December 26, 1929 after a storm draped the walkway and tower in ice. The lighthouse survives today and is owned by the city.

Caption: Minot’s Ledge Light off Cohasset, Massachusetts, often becomes shrouded in ice from winter storm waves. The sentinel stands on a submerged rock ledge and has stood watch since 1860.

Caption: St. Joseph Pierhead Light on Lake Michigan has dazzled the public throughout its career with strange and marvelous ice formations sculpted by spray and wind. This is the lighthouse circa 1950.

Caption: Ice plagued the lighthouses on the Hudson River, New York, prior to ice-breaking technology. A 1961 image shows a Coast Guard icebreaker approaching the Esopus Meadows Lighthouse.

The Ashtabula Lighthouse

The many breakwater and pierhead lights on the Great Lakes also ice up in winter. Just 50 miles east of Cleveland, the breakwater lighthouse at Ashtabula was totally sheathed in ice in November 1928. The Lighthouse Service Bulletin for that y ear described the storm :

On January 20, 1928, a gale from the westward set in with the temperature steadily falling. This gale continued through the next day, with the temperature reaching zero. Due to the open water and force of the gale, the sea and spray froze to the lighthouse crib and buildings, completely encasing the entire structure in heavy ice…. The structure is over 52 feet high above water, which shows the height of the seas and spray.

Relief keepers, who had arrived only days before to allow the regular Ashtabula lightkeepers a few days vacation ashore, panicked when the ice built up quickly and imprisoned them inside the tower. Terrified, they radioed the Lighthouse Depot at Cleveland for help and began working on the ice-locked door with picks and hammers.

Meanwhile, the regular keepers made their way from shore over the slippery breakwater and began chiseling away at the ice from the outside. A supply tender arrived several hours later and pumped hot water over the lighthouse entry door to free the men.

The Colchester Reef Light

Lake Cham plain has often been called “The Sixth Great Lake.” Like its Midwest sister lakes, it also experiences harsh winters with extreme cold and ice. The lake has only a few lights still operating today , but in its heyday as a shipping corridor for lumber and slate, it had about a dozen lighthouses. The most exposed was Colchester Reef Light, a quaint house and lantern sitting atop a stone caisson to mark three dangerous reefs between the

lakeshores of Vermont and New York. Knowing the sentinel would have to endure high winds and winter’s freeze, its walls were strengthened with one-and-one-half-inch thick iron rods. The stout construction paid off when the lake froze over, but also when the ice thawed, broke up, and began to move.

Many lightkeepers tended Colchester Reef Lighthouse, but August Lorenz was the most intrepid. A bachelor who enjoyed winter solitude, he could be seen skating on the lake around the lighthouse, trudging the four miles to shore in snowshoes, or ice fishing. One afternoon in November in the early -1920s, before the lake had completely frozen, he was rowing home from the mainland where he had picked up supplies. A stout wind whipped up a spray , and by the time Lorenz reached the lighthouse, he was completely covered in ice, and his feet were frozen to the bottom of the boat. He used his pocketknife to free him self.

Worse was a February day in 1923 when an unseasonable warm front initiated an early thaw and ice began to mov e on the lake. Large chunks slowly passed the lighthouse and ground against the stone foundation. After supper, as Lorenz was working in the lantern, a loud bang jarred the entire structure. A few seconds, later the kitchen wall gave way as an ice floe drove into the lighthouse. Lorenz rushed downstairs in time to see it recede into the night. The keeper did what he could to cover the hole. The next morning he discovered his dory had been torn from its davits and was sitting some distance away on a cake of ice. He was able to retrieve it by hopping from ice cake to ice cake and dragging it back to the lighthouse with a hooked pole.

The Mid-Atlantic and New England

The bays, sounds, and rivers of the Mid-Atlantic and New England were plagued with ice during the coldest winters. In these bodies of water, the structures most at risk were the screwpile-style lighthouses in the open water of the Chesapeake Bay — curious little lighthouses perched on iron legs that were literally screwed into the bay floor. Ice jams slammed these structures and did serious damage, sometimes shearing them off their legs. The Annual Report of the Lighthouse Board noted a particularly tough winter in February 188 for the keepers of Sharps Island Lighthouse off the southern tip of Tilghman Island:

The structure was lifted from its foundation and thrown over on its side and carried away by ice. The keeper and his assistant clung to the floating house and … drifted in the bay 16½ hours without fire or food, always in imminent danger.… [the lighthouse] grounded however, full of water, on an island

shortly after midnight at high tide.

Twelve years later, another big ice jam in January 1893 ruined three screwpile lighthouses in the Chesapeake Bay at Smith Point, Solomons Lump, and Wolf Trap. The first two were damaged but not destroyed. The fearful keepers at Solomons Lump stuck to their post, but at Smith Point the men abandoned the lighthouse and lost their jobs as a consequence. The Wolf Trap Light, situated at the entrance to Winter Harbor, was sheared off its legs and thrown into the bay . The two keepers escaped to their boat moments before the calamity . The lighthouse, with only its upper part above water, drifted for almost a day before being lassoed by a cutter and towed to shore.

Ice truly can be a contest between nature and man-made structures, and lighthouses feel the brunt of this bittersweet winter punishment. But not every winter blast causes mayhem. The late Frank Jo Raymond, keeper at Long Island Sound’s Latimer Reef Lighthouse in the 1920s, made peace with the snow and ice. When winter settled over the cast-iron, caisson-style tower and locked the doors and windows with its icy fingers, Raymond stoked the coal stove, made a big pot of coffee, and picked up his paintbrush. His oil paintings fetched extra income in the summer months when tourists swarmed the nearby shores.

One storm in 1925 kept Raymond sequestered inside for several days. During that time, he kept the light going, as required, and painted a fantastic winter scene on the circular walls of the tower’s interior. Unfortunately, when the lighthouse inspector came to visit a few weeks later to assess the storm dam age, he ordered Raymond to paint over the mural. Regulations said all interior walls had to be white.

“I smiled and did as I was told,” Raymond said in a 1987 interview. “But as soon as the next storm came, I picked up my paintbrush and went at it. You had to see that lighthouse in winter to believe it — so beautiful.”

Caption: Thomas Point Shoal Light is the only screwpile lighthouse that remains in service on the bay. Rocks piled around the iron legs of the lighthouse help protect it from ice.

Caption: The first lighthouse at Sharps Island in the Chesapeake Bay was a screwpile design. It was destroyed by drifting ice in 1881 and was replaced by a caisson tower a few years later, but the annual assault by ice has caused the lighthouse to lean. Even so, it remains in service.

A PDF copy of the file is available here.

On this website there are some more beautiful photos of ice-encrusted lighthouses on Lake Michigan. Really eerie!

[private][nggallery id=86][/private]

©2 0 1 0 Taylor & Francis Group · 325 Chestnut Street, Suite 800, Philadelphia, PA · 19106 heldref@taylorandfrancis.com

http://www.weatherwise.org/Archives/BackIssues/2011/November-December2011/Sentininals-full.html