As most of you know I am living in the Philippines now. There are lighthouses in the Philippines, and some of the ancient structures are being rebuilt as historical monuments by the Coast Guard.

As most of you know I am living in the Philippines now. There are lighthouses in the Philippines, and some of the ancient structures are being rebuilt as historical monuments by the Coast Guard.

As far as I know there are no manned lighthouses here. Most of the lighthouses are automated beacons of low power used by fishermen to return back home, like the one at the left that I discovered at Apatot Beach, San Esteban, Ilocos Sur, Philippines. This is listed in the Lightstations Northern Luzon Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) webpage.

Here is another one closer to my hometown of Candon City, Ilocos Sur. I found this lighthouse by the sea in the Darapidap area. It looks a lot older than the one above.

Here is another one closer to my hometown of Candon City, Ilocos Sur. I found this lighthouse by the sea in the Darapidap area. It looks a lot older than the one above.

It was found in the town square. As it is not very high I assume it is only used by the fishermen. This type of tower may be used all over the islands. This is listed in the Lightstations Northern Luzon Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) webpage.

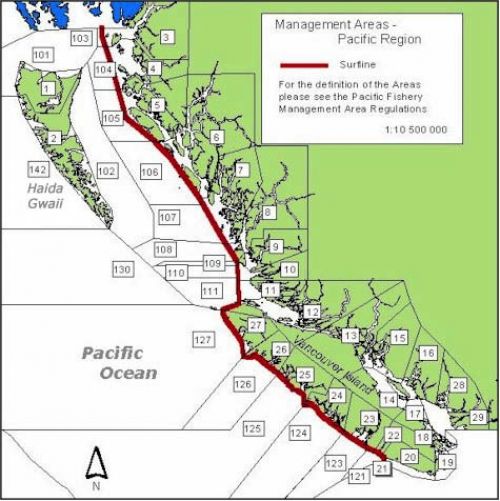

The following interactive embedded map is from ArcGIS Explorer. This online program allows one to create personalized maps about various subjects around the world. This one is about Philippine lighthouses listed on the PCG website. I have marked with coloured circles the various lighthouses, RED for manned stations, BLACK for automated stations, BLUE for ruins, and ORANGE for lights that are tended by PCG living in the area.

Clicking on the dots brings up a name card with information.

View Larger Map

One article which caught my interest is The Lost Lighthouses of Ilocos Sur (part 4)

[private]

By Frank Cimatu, Leoncio Balbin Jr.

Inquirer

Last updated 01:06am (Mla time) 07/26/2006

Published on Page A15 of the July 26, 2006 issue of the Philippine Daily Inquirer

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth of a series of reports on lighthouses in Northern Luzon. The Inquirer is featuring these century-old structures to highlight their importance to the country’s northern sea lanes and call public attention to their neglect.

ILOCOS SUR is one of the oldest provinces in the country and an important trading center for the Spaniards. The Chinese pirate Limahong used to pillage the settlements there and later traded with local folk four centuries ago.

The province has an extensive shoreline, but many residents are wondering why they can’t spot a lighthouse as imposing as Cape Bojeador at the tip of Ilocos Norte.

But the lighthouses of Ilocos Sur are there, albeit forgotten and neglected. Now, local officials are calling for the restoration of the “lost beacons.”

The once important lighthouses during the Spanish times are in Narvacan, San Esteban and Sinait towns, Vice Gov. Deogracias Savellano said.

“These are brick monuments of history. As much as we wanted to restore them, we have no funds yet for this project,” Savellano said.

The structure in Narvacan may not even be a lighthouse but a watchtower.

Michael Canosa, 42, a resident of Barangay Sulvec, said the old brick facility in their backyard was built during the time of the Spaniards.

Canosa said based on the stories shared by his relatives, his great grandfather, Lope Canosa, was among the recruited soldiers who served as sentry under the Spanish government.

The watchtower was used to warn residents of the arrival of pirates.

“They would blow a horn to signal the arrival of the pirates for residents to prepare,” Canosa said.

The watchtower is deteriorating; its bricks chipping off due to exposure to the elements. The ownership of the area where the watchtower sits is also being disputed in court between the Canosas and the municipal government.

Reminders

Ilocos Sur Rep. Eric Singson has initiated moves to restore the lighthouse in nearby San Esteban. “Even if these lighthouses are obsolete, they are still important reminders of the glory that was Ilocos Sur,” he said.

He said lighthouses used to draw the community together. To make his point, he converted the Parola lighthouse in Barangay Darapidap in Candon City into a promenade. The lighthouse was built in the 1950s.

A boardwalk, a fountain and a mini-stage were inaugurated in the area in April. Bands perform onstage during the balmy summer nights. Singson said an amusement park would be added later.

The 20-meter lighthouse is useful to fishermen in the town, Eduardo Villanueva, chair of Barangay Darapidap, said. “It serves as a reference for fishermen during blackouts.”

At first, they used kerosene for the beacon until 1971 when electricity was tapped in the village.

Another modern lighthouse is in Cabugao town.

Savellano said the historic Dardarat lighthouse also guided fishermen’s voyages to the Salomague port. Because of the port, Salomague is among the few Ilocos villages found on ancient mariner’s maps.

“During the American occupation, it served as a mooring place for USS Manauili that ferried thousands of mostly Ilocano residents across the Pacific to work at sugar plantations in Hawaii and California,” Savellano said.

Now leased to a private corporation, it is the transshipment port of goods and products to Taiwan. It is also the unloading point of commercial fishing vessels. [/private]

101-year-old lighthouse is Bolinao’s landmark (part 3) and more photos here.

[private]

http://newsinfo.inq7.net/inquirerheadlines/regions/view_article.php?article_id=6949

By Yolanda Sotelo-Fuertes Inquirer Last updated 06/28/2006

Published on Page A19 of the June 28, 2006 issue of the Philippine Daily Inquirer

Editor’s Note: This is the third of a series of reports on lighthouses in Northern Luzon. The Inquirer is featuring these century-old structures to highlight their importance to the country’s northern sea lanes and call attention to their neglect.

FOR 101 years now, the Cape Bolinao lighthouse stands proud atop Punta Piedra Point in Barangay Patar in Bolinao, Pangasinan, guiding ships and vessels cruising the international passage along the South China Sea.

Nestled amid trees, the lighthouse was built in 1905 by Filipino, British and American engineers. It is one of the five major lighthouses in the country and the second tallest, next to the Cape Bojeador lighthouse in Burgos, Ilocos Norte. It has become a prominent landmark that tourists frequent.

The 30.78-meter (101-foot) tower provides a panoramic view of the blue sea and white beaches, offshore reefs and rock formations, as well as rolling verdant hills. Once in a while, a passing vessel dots the sea, an international route of vessels going to Hong Kong, Japan and the United States.

The 140-step winding stairway of the tower leads to the illumination room, 76.2 m above sea level. According to Pedro Honrada, the lighthouse’s head keeper, the lantern is visible 44 kilometers away, guiding seafarers (led toward this area by a lighthouse in Zambales) toward the lighthouse in Poro Point, La Union.

The late Bolinao historian Catalino Catanaoan said the original light machine was manufactured in England, while the lantern, with three wicks and chimneys, was imported from France.

“Filipino machinists were able to copy the original [when they repaired it]. The light machine is rotated by a system of gears like that of a big clock with a pendulum of weights, winded and suspended with steel cable,” he said.

Kerosene fuel

The lighthouse was fueled by kerosene during its first 80 years of operation. When the Pangasinan I Electric Cooperative extended its lines to Patar, the lanterns were powered by electricity.

In 1999, the lighthouse was renovated through a loan package extended by the Japanese government to the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG), which is in charge of the facility. Aside from repairing and repainting the tower, the assistance included setting up solar panels, a new apparatus and two beacon lights. The panels recharge the lights.

The lighthouse has also been getting the attention it deserves from the municipal government.

In June last year, Mayor Alfonso Celeste entered into a memorandum of agreement with the PCG to “adopt” the Cape Bolinao lighthouse to ensure its preservation and maintenance, under the PCG’s “Adopt a Lighthouse Program.”

Under the MOA, the PCG continues to be the sole owner of the lighthouse. It has the right to deny entry into the area during emergency cases and is responsible for the operation, repair and regular maintenance of the beacon light and its supporting mechanisms.

On the other hand, the local government will take charge of rehabilitation and maintenance of the immediate vicinity (except that of the beacon, solar panels and other equipment), provide maintenance personnel, and protect the facilities from vandals.

Cultural heritage

The local government is also tasked with promoting the declaration of the lighthouse as a cultural heritage.

Already, the lighthouse compound has been spruced up. The uphill road leading to the tower has been paved with the help of Pangasinan Rep. Arturo Celeste. A view deck has been put up in the area.

The rehabilitation of the administration building and a public bath was funded by the Department of Transportation and Communications.

Brunner Carranza, municipal planning and development officer, said a worker assigned by the local government keeps the area clean all day.

While the lighthouse has become a tourist attraction by itself, it has failed to do its “job” of guiding sea vessels at night, Honrada said.

In early November 2004, the beacon lights started to dim until it finally shut off on Nov. 8.

“The batteries bogged down,” Honrada said. He has been following up with the PCG navigation command the repair of the batteries that cost about P1 million—to no avail.

“My wish is that before I retire [in October], the lighthouse will be working again,” Honrada said.

[/private]

Faro de Cabo Engaño (part 2)

[private]

Wednesday, June 14, 2006

Cagayan’s guiding light won’t let darkness fall

http://news.inq7.net/regions/index.php?index=2&story_id=79029

By Melvin Gascon

Inquirer

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the second of a series of reports on lighthouses in Northern Luzon. The Inquirer is featuring these century-old structures to highlight their importance to the country’s northern sea lanes and call attention to their neglect.

TERESA Jamorabon was beaming as she recalled the years when living at the Faro de Cabo Engaño was everything she, her husband and their brood of nine could only dream of.

Her husband, the late Gregorio Jamorabon, was among the longest-serving lighthouse keepers in the Cape Engaño light station on Palaui Island at the northeastern tip of the archipelago.

From 1946 to 1968, the Jamorabons called the Cape Engaño lighthouse their home.

“It was wonderful. We were like living in paradise; we had everything we needed. We were happy because best of all, my husband was working while he had with him his family,” Jamorabon, 80, said.

The Cape Engaño is one of the 27 major lighthouses in the country, which, until now, continues to play a crucial role in navigation, especially for ships traversing the Babuyan Channel in Northern Luzon and the Pacific Ocean. It is under the supervision of the Department of Transportation and Communications, through the Philippine Coast Guard’s lighthouse division.

Perched on the northern edge of the island, Cape Engaño is still regarded as one of the most beautiful lighthouses in the country.

Built in 1888, mostly by Filipino laborers, the structure has withstood the Spanish-American War and World War II, as well as the wrath of scores of typhoons.

Fortress-like

The fortress-like station sits atop a hill 92 meters above sea level, overlooking the Cape Engaño cove on the east, the clear waters of the Babuyan Channel and the Dos Hermanas (Two Sisters) Islands on the north, and the vast Pacific Ocean on the west.

It is said that Spanish seafarers who first set foot on the cape were so enthralled by its natural beauty that they named it Engaño.

From the Santa Ana town proper, the station can be reached by a 30-minute boat ride from the Barangay San Vicente port, going northward and docking at the white sand beach of the Cape Engaño cove. It takes 20 minutes to hike the top of the hill.

The station has four major structures: The one-story main pavilion that serves as the office and the workers’ quarters; two smaller identical buildings, which used to be the kitchen; and the storage and powerhouse.

At the center is the 11-m (47-foot) octagonal tower, whose protruding attic (the platform on which the crown and lantern rest) is visible from all angles around the cape.

Lighthouse families

According to Jamorabon, the complex used to shelter seven crew members tasked with maintaining the lighthouse. Their families lived with them.

It used to be like a castle, she said, describing how for a long time, it stood in all its grandeur, and how its lights used to glow at night like a modern city in the middle of the jungle.

To live there was to be the object of envy for many people in Santa Ana, according to Jamorabon, because, for one, it was the only place in the area where residents enjoyed electricity.

“Santa Ana was still then a dense jungle, so that when people came here, it was like they had gone to the city,” she said.

Jamorabon described how well the government took care of the lighthouse keepers and the station. The workers’ families lived harmoniously in separate rooms, but under one roof.

Their rations—rice, beans, noodles, cooking oil and kerosene—arrived every month and were shared equally among the workers, regardless of rank, she said.

Imelda Jamorabon-Leaño, 47, Jamorabon’s eighth child, recalled how she and the other workers’ children, coming home from school every weekend or during Christmas or summer breaks, found joy in watching ships as these arrived from the Pacific Ocean and the Babuyan Channel.

The lighthouse keepers also raised goats to augment their food. The forest and the sea were also abundant sources of food, said Leaño, now a grade school teacher at the Santa Ana Central Elementary School.

But the light station received substantial attention from the government only until the early 1980s, said Jamorabon, adding that assistance dwindled with the change of administrations.

She has not set foot again on Cape Engaño since her husband retired from service in the 1960s.

Sorry state

But Jamorabon feels that pinch in her heart whenever she hears people’s accounts of what has become of the lighthouse.

Today, the light station sits forlorn on the island and is in a sorry state of decay and neglect. It continues to be destroyed by elements, aggravated by the government’s apparent apathy to preserve this cultural and historical treasure.

The windows, doors and roof of the main pavilion, as well as that of the kitchens and the storage rooms, have been destroyed, leaving only the two-foot thick granite walls intact. The rusting power generators are now pieces of junk.

The tower has also fallen victim to thieves and vandals. The eight bronze lion busts, which used to cling onto the tower’s eight corners underneath the attic, have been stolen. Even its bronze marker was also pried off from the front wall of the pavilion.

The cisterns or concrete reservoirs, where lighthouse keepers used to collect rainwater for drinking and household needs, are no longer in use.

Treasure hunters had dug a tunnel underneath the main building and graffiti dominate the buildings’ white granite walls.

But all is not lost for the Cape Engaño light station.

Thanks to dedicated lighthouse keepers like 51-year-old Cesario Sumibcay, who, despite the low pay and lack of adequate attention from the government, continues to ensure that the lighthouse remains functional.

The Coast Guard has replaced the lantern with a solar-based lighting mechanism, which required little human intervention.

Gov. Edgar Lara is optimistic that a joint restoration project that the provincial government was embarking on, in partnership with the Cagayan Economic Zone Authority and a number of nongovernment organizations, would restore the luster of Cape Engaño.

“This is why we are opening up the place to ecotourism to raise public awareness about the need to preserve the lighthouse and possibly attract future investments on the island,” he said.

http://news.inq7.net/regions/index.php?index=1&story_id=78959

http://news.inq7.net/regions/index.php?index=1&story_id=78959

By Cristina Arzadon

Inquirer

BURGOS, Ilocos Norte — The over a century-old Burgos lighthouse (known locally as the Cape Bojeador lighthouse) is not just a beacon to seafarers.

It is also a source of provincial pride after the National Museum declared it a national cultural treasure in December 2005.

Perched on Vigia de Nagpartian hill, the lighthouse, however, cries out for national attention as it continues to battle the elements that have been battering it the last 114 years.

The structure is composed of a 160-m tall light tower, living and office quarters and a courtyard.

Completed on March 30, 1892, the lighthouse was built by Guillermo Brockman from a design by Magin Pers y Pers. It is made of locally fabricated bricks and accented with cast metal grillwork.

Octagonal tower

Motorists driving north through the province of Ilocos Norte can catch sight of the lighthouse which dominates the Burgos skyline.

Lone lighthouse keeper Vicente Acoba Sr. is kept busy by the steady stream of visitors who climb the steep steps leading to the tri-level complex that supports the octagonal lighthouse tower.

Panorama of the sea

From its top, one can easily take in the sweeping panorama of the sea and the surrounding countryside.

“Sea vessels making the voyage from the Babuyanes Channel toward Hong Kong or Yokohama (Japan) can’t miss the lighthouse,” Acoba told the Inquirer.

Based on an initial study commissioned by the National Museum, the base of the lighthouse needs to be strengthened before the structure could be improved.

The building is in good condition but the living quarters and offices need to be repaired.

At one point, Councilor Joegie Jimenez, chair of the Burgos Tourism Council, said, archeologists from the University of the Philippines who did research on the lighthouse excavated a site where the kiln that was used to fire up the bricks that make up the structure was buried. Old bricks were also found in the hole.

Jimenez said the tourism council plans to put up a landmark at the site.

“We need to make people aware of the need to save the lighthouse. This is the town’s single, most important structure,” he said.

Jimenez said efforts to preserve the lighthouse complex were continuing after initial restoration work for the roofing was completed.

Symbol of Spanish times

Donations, mostly from Burgos residents here and abroad, helped restore the town’s most enduring symbol of the Spanish era.

The funds, however, were not enough to restore the entire structure.

“We need to have more improvements. We only managed to repair the rotting roof and upgrade its wooden support,” Jimenez said.

“We thought that by being declared a national treasure, the national government would pay attention to its preservation by helping produce funds,” Jimenez, a board member at the time, said.

He said the lighthouse was in bad shape after being whipped by Typhoon Feria in 2001.

“The iron sheets were flapping while several glass panels surrounding the lighting device were shattered.”

“The structure itself was left rotting,” Jimenez said.

He said the foundation is preparing a rehabilitation proposal it will submit to the National Commission for Culture and the Arts for funding support.

1,000-postcard campaign

The proposal would contain a technical study on what kind of preservation the lighthouse should undergo.

The roof improvement was made possible through the “Save the Cape Bojeador Lighthouse” campaign that Jimenez and the Cape Bojeador Development Foundation initiated in 2003. Ilocos Norte Gov. Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is the foundation’s honorary chair.

Burgos Mayor Benjamin Campañano caused the placing of streetlights in the courtyard, which serves as the main entrance to the complex.

Jimenez reproduced some 1,000 postcards, touting the campaign, which were distributed to Burgos natives living in other countries.

The campaign raised some P2.2 million from contributions and from provincial government funds.

It was the second rehabilitation the lighthouse underwent since its construction in 1892. The first improvement was done in 1982.

[/private]

Lonely Sentinels of the Sea: The Spanish Colonial Lighthouses in the Philippines (part 1)

[private]

by Manuel Maximo Noche Lopez Del Castillo

In the 1880’s, the Spanish Colonial government undertook massive construction frenzy. Its main goal: to protect the ever-increasing maritime trade the Philippines was then experiencing. With the end of the famed Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade, the Philippines was opened to a wider network of international trade. This necessitated more shipping routes to and from the islands, as well as more connection between Manila and beyond. In the absence of modern satellite or radar technology, navigators at that time relied heavily on astronomy; on stars to map and chart their courses. Though medieval, this proved adequate, considering that explorers were able to find their way around the globe with nary an incident. But to further ensure the safety of the galleons – by these time coal-burning transport ships laden with precious commodities – further guides were needed to bring the ships safely into harbor or open waters. This brought about the construction of faros (lighthouses) throughout the archipelago.

Lighthouses in the Philippines are nothing new. The oldest lighthouse in the country was erected way back in the 16th century, almost at the onset of Philippine colonization. This lighthouse, located at the mouth of the Pasig, guided navigators to the banks of the river, which served as the main port of Manila, the capital of colonial Spain in the Orient. Centuries would progress with the Philippines comfortable with the wealth that the Galleon trade would bring, but not a single lighthouse except for the one located in the mouth of the Pasig as well as fires lit on top of Corrigedor Island was built

By the 19th century, towards the end of Spanish colonization, the Spanish Colonial Government undertook a massive lighting of our seas. The Plan General de Alumbrado de Maritimo de las costas del Archipelago de Filipino or the “Masterplan for the lighting of the Maritime Coasts of the Philippine Archipelago” was undertaken by the Inteligencia del Cuerpo de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos or the “Corp of Engineers for Roads, Canals and Ports. The task to light the seas and channels of the country to guide ships in and through the most important sea channels to the Ports of Manila, Ilo-ilo and Cebu. This plan, which was drafted in 1857, was immediately set into action with the preparation and eventual construction of roughly 70 lighthouses allover the archipelago. Of these 22 are of major construction works while the rest were of lower classification lights.

Spanish Engineers were tasked in the preparation and supervision of these lighthouses. Engineers such as Guillermo Brockman, Magin Pers, Eduardo Lopez Navarro, Ramon Ros, Enrique Trompet Vinci, Alejandro Olano designed structures that were functional, comfortable and beautiful as well. These structures located in the most beautiful and spectacular sites, lonely isolated islets, cliffs, barren rock outcrops, bluffs, capes and points, are testament to the commitment the Spanish Colonial government had on the Philippines to modernize it and make it competitive at the dawn of the 19th century.

Designed in the prevailing renaissance revival style as well as the Victorian Style of Architecture, these structures, composed of tower, pavilion and service buildings were built to house the lights as well as the keepers who would man them. The tower, the most significant part of any lighthouse was made strong and tall to ensure visibility at any given condition. The pavilion on the other hand was designed to accommodate the lighthouse keeper and his family whose role it was to ensure that the lights were lit every evening and that the prisms or Fresnel Lens are rotating. Two service buildings, usually flanking a grilled courtyard would contain kitchens and almacenes or storage rooms for the combustible materials that were used to light the tower. An outhouse situated a few meters away from the complex served the toilet needs of the keepers.

Different towers were designed by the Corp of Engineers. The most significant are those made of masonry of either brick or stone. Of the lighthouses visited during the course of this research, 13 towers were built of masonry. Faro de Cabo Engaño, Isla Palaui, Santa Ana, Cagayan; Faro de Cabo Bojeador, Burgos, Ilocos Norte; Faro de Punta Capones, Islote de Capon Grande, San Antonio, Zambales; Faro de la Isla de Cabra, Lubang, Mindoro Occidental: Faro de Rio de Pasig, Binondo, Manila; Faro de Isla Corrigedor, Cavite; Faro de Punta Malabrigo, Lobo, Batangas; Faro de Cabo Santiago, Calatagan, Batangas; Faro de Islote de San Bernardino, Bulusan, Sorsogon; Faro de Punta Bugui, Aroroy, Masbate; Faro de Isla Gintotolo, Balud, Masbate; Faro de Cabo Melville, Isla Balabac, Palawan; and Faro de Punta Capul, Capul, Samar del Norte. Towers of metal were also fabricated, these towers known as Tourelle, were made and manufactured in France and would easily be assembled on site. Such towers are found still standing at Luz del Puerto de San Fernando, San Fernando, la Union, Luz de Isla Bagatao, Magallanes, Sorsogon, Faro de Islote de Siete Pecades, Dumangas, Ilo-ilo and Faro de Punta Luzaran, Nueva Valencia, Guimaras. Though the towers of Faro de Islote de Manigonigo, Carles, Ilo-ilo, Faro de Sibulac-Babac de Gigantes, Estancia, Ilo-ilo, and Faro de Isla Calabazas, Ajuy, Ilo-ilo have been replaced with modern aluminum towers and lights, they originally contained metal Tourelle towers. Metal towers too were used for Faro de Islote de Tanguingui, Bantanyan, Cebu, and Faro de Islote de Capitancillo Tobogon, Cebu, supported by metal framework, these towers were able to rise taller than the Tourelle, which had a standard height of 6 meters.

The main pavilion of the Lighthouse, which is elevated from about a meter to over 3 meters above ground is used primarily as an office for the assigned engineers as well as living quarters for the lighthouse keepers and their families. For 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and even to some extent 6th order light stations, complete dwelling facilities are provided for. Though those, which are within easy access to communities, are provided only with the most basic of shelters, as surmised in the Luz del Puerto de San Fernando, and Luz de Isla Bagatao. Both being 6th orders stations, its original quarters were of light materials, only during the American Commonwealth Period were permanent quarters built. The pavilions were built of the same materials as the tower, either locally sourced granite or locally made bricks. Hard wood, such as Molave, Tindalo, and Narra was used for the beams, joists, trusses, floors, nailers, doors and windowsills. Walls were plastered and painted with some examples stenciled with interesting patterns. Marble, clay tiles or plain cement finishes were used for the verandah. Decorative Metal Grilles surround the fence, balconies as well as the bottom level of windows. Corrugated iron sheets cover the roof. Most 1st to 3rd order lighthouses are equipped from 2 to 4 quarters, with each quarter provided its own receiving area. An office for the on-duty engineer is also provided. This office which normally has a view of the sea, is also used as the lighthouses’ watch room. In most cases, this watch room is accessible to the tower. A hallway, which bisects the pavilion in two, is commonly provided for. This enables the engineers and keepers easy access from their rooms to any part of the building. A verandah is situated either in front or at the rear of the building. For Faro de Islote de San Bernardino, Faro de Punta Malabrigo, Faro de Punta Bugui, Faro de Isla Gintotolo and the Faro de Punta Capul, a surrounding verandah is provided. Finally basic furnishing such as, camas, escritorios, mesas, sillas, armarios, and estantes are provided

Today, these lighthouses built by the Corp of Engineers of the Spanish Colonial Government over 100 years ago are in various states of disrepair or ruin. Some are in admirable condition such as those of Faro de Cabo Bojeador, Faro de Punta Malabrigo, Faro de Cabo Santiago, Faro de Isla Gintotolo, Faro de Siete Pecados, Faro de Cabo Melville (which still retains its original 1st order Fresnel Lens and could be made operational again with minor repair work), and Faro de Isla Corrigedor, which was restored by the Cooperacion Español, while others are in need of immediate attention, such as Faro de Punta Capones, Faro de Sibulac-Babac de Gigantes, Faro de Isla Cabra, Faro de Islote de San Bernardino, Faro de Punta Capul, and Faro de Punta Bugui (with its 3rd order lens still intact). Though some are still repairable, there are a few which are today sadly in total ruin. Lighthouses such as those in Cabo Engaño, Islote de Tanguingui, Islote de Capitancillo, Punta Luzaran, Islote de Manigonigo, and Islas Calabazas are in total ruin and would need massive amounts to restore and made habitable again.

But what is the point of restoring, when these lighthouses do not function the way they did a hundred years ago. True, these lighthouses are still needed to light our seas. The tower receives numerous funding for its modernization and upkeep, with most towers retrofitted with modern solar light, thus necessitating the removal of historic bronze cupolas and its inch thick Fresnel Lens. With the towers automated, the need for lighthouse keepers to man such structures is obsolete. Today, lighthouse keepers have an easier task, visiting towers only once in a while to replace busted bulbs and to do minor maintenance work. But with funds scarce, the damages wrought by over 100 years is too daunting.

The Spanish Colonial Lighthouses built over 100 years ago still serves its master well. Guiding ships to their ports of call, these structures, stripped of their dignity still stand proud in their lonely windswept location. Yet even with time and the elements acting against them, the beauty that the Spanish Engineers erected on our soil cannot be erased. It is time that we, the inheritors of this patrimony should do what we can to ensure its survival for the next 100 years. For these lights not only lit the souls and imaginations of those who chanced upon them they also guided a nation to progress.

The essay is based on a report conducted by the author on Spanish Colonial Lighthouses in the Philippines through a grant received in 1998 from the Ministry of Education and Culture of Spain “Towards a Common Future” and the Center for Intercultural Studies, The University of Santo Tomas. Throughout the study, from 1998 to the present 24 Spanish Colonial Lighthouses all over the country were visited and studied. A detailed assessment of their conditions was conducted and recommendations made to the Coast Guard of the Philippines for their eventual restoration.

[/private]

In the website article below they state:

Most of the lighthouses, usually charged by solar power, are not manned 24/7. While many have timers and automatically turn on at night or when the skies turn dark, others have to be manually turned on by a PCG civilian employee.

There are numerous articles I have mentioned on Philippine lighthouses. One of the best is Sentinels of heritage guide PH’s progress, light its soul which describes the Spanish influence on many Philippine lighthouses.

Apart from serving as signal stations and beacons for ocean-going ships through the centuries, a few lighthouses of the Spanish period, particularly those in the Visayas and Mindanao, served as watchtowers against pirates and slave traders.

The Paris-based International Council on Monument and Sites (Icomos) recognizes the heritage value of the Philippines Spanish-era lighthouses, which are mainly of Victorian design.

Constructed by Spain’s renowned Inteligencia del Cuerpo de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos (or the Corps of Engineers for Roads, Canals and Ports), the lighthouses were built to protect burgeoning maritime trade in late 19th-century Philippines.

These structures located in the most beautiful and spectacular sites, lonely isolated islets, cliffs, barren rock outcrops, bluffs, capes and points, are testament to the commitment the Spanish colonial government had in the Philippines to modernize it and make it competitive at the dawn of the 20th century, Noche wrote in an article in the Icomos website.

In the above article they mention the following lighthouses:

Capones Island Lighthouse on Capones Grande Island off the coast of San Antonio, Zambales

Cape Bojeador in Burgos, Ilocos Norte

Cape Engaño in Sta. Ana, Cagayan

Batanes’ Sabtang Island

Faro de Punta Malabrigo in Lobo, Batangas

Another famous lighthouse is located at Poro Point, San Fernando, La Union. This has now become a tourist attraction and has been mentioned in this article:

Poro Point Lighthouse, a Light for Prosperity

Another article and another lighthouse is Capturing The Beauty of Capitancillo Islet In Pictures from a friend of mine Rusty Ferguson living in Bogo, north of Cebu, Philippines.

Capitancillo Lighthouse

Another lighthouse mentioned on the above Facebook site is:

Bagacay Point Lighthouse

Another website lists Lighthouses of the Northern Philippines in which are mentioned:

Matoca Point Lighthouse

Batangas Customs House

Cape Santiago (Punta de Santiago)

Fortune Island Lighthouse

and there are many more listed on the website with more references.

One other website that lists one hundred and ten (110) Philippine lighthouses is the Amateur Radio Lighthouse Society.(ARLS)

So there you have it – a lot of lighthouses, none of them manned, some being repaired. Is it worth a trip to the Philippines? Definitely a big YES!