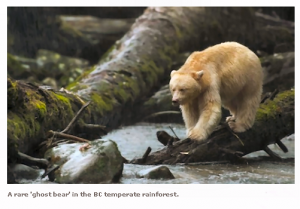

A rare white ‘spirit bear’ in the BC temperate rainforest. Photo: Ian McAllister / pacificwild.org.

In the sanctuary of the White Bear by Canadian Poet Lorna Crozier

17th November 2013

Poet Lorna Crozier vists the Great Bear Rainforest in BC, Canada and finds a fragile paradise imbued with myth, meaning and magic for local indigenous peoples.

Above the stench of rotting salmon, my smell has been drawn into a grizzly’s nostrils, through the nasal passages inside his long snout. Part of me now lives inside the mind of an omnivorous animal whose Latin name ends with horribilis.

The bear is here for the salmon, who have returned to the rivers of their birth to spawn and die. We’re here for the bears.

Photographer/filmmaker Ian McAllister has joined my husband Patrick and me on our first morning to help introduce us to his home turf, the Great Bear Rainforest, a tract of land that follows B.C.’s coastline from the tip of Vancouver Island to the Alaska Panhandle. He and his wife Karen run the Pacific Wild conservation group to protect this astonishing piece of wildness that they’ve known intimately for over twenty years.

The largest intact temperate rainforest in the world, the traditional territory of the Kitasoo / Xai’xais First Nation, this region is only two short flights from Vancouver. But we are as far from a city, as far from ordinary life, as you can get. . . . more

This essay originally appeared in Toque & Canoe, and in Counterpunch.

[private]With seven others, we’ve been bounced across the ocean to our riverside destination in an old forestry boat. At home, most of us can’t spare the time to meet a friend for coffee, but here we’ll wait side by side, motionless and quiet, for several hours in the drenching rain.

Two guides armed only with pepper spray keep watch over us. They assure us they’ve never had to use it. Their confidence and my excitement make me tuck any fears I have away – into a back jeans pocket I can’t reach under my layers of hoodie, vest, jacket and rain gear.

All of us crouch with binoculars and cameras, careful not to sink our knees into a salmon. Hundreds of them, tossed by bears from the river, are turning into a foul mush. When the grizzly appears again, about twenty feet across from us on the other shore, we know Ian is getting the best pictures. We keep snapping anyway.

Our group is staying at the First Nations-owned and operated Spirit Bear Lodge located on the ocean’s edge in the fishing village of Klemtu.

Through its tall windows, we scan what looks like a National Geographic documentary. Pointing out seals and eagles, we and the other guests, most of them from Europe, crowd around the window like kids around an ice-cream truck.

Maybe if we’re lucky, at dusk, we’ll see one of the wolves unique to the western coast. Along with deer, they catch salmon.

The lodge is modeled on the traditional long house and it’s named after the elusive white bear called the ‘Spirit Bear‘.

Raven, the traditional story goes, made one out of every 10 black bears white to remind us of the ice age. This unique creature is here to make us grateful: the world wasn’t always as green and lush as it is today.

Every morning, rainforest life generously comes to meet us. Five senses aren’t enough to take it all in.

Isn’t this what Canada’s all about? Barely inhabited, out-of-the-way places that remind humans who we were before we became so fearful, so tame? Before we became so destructive as a species?

As twilight falls, we return to the lodge by boat for its scrumptious dinners, the halibut so fresh that the name of the man who hooked it and the date he did are listed on the menu. Manager Tim McGrady – fierce in his love of this watery ecosystem – greets us at the dock and asks what we’ve seen.

Over the 12-foot-long cedar dinner table, Patrick and I go on and on about a mother and a baby humpback, the mother slapping her tail repeatedly on the taut skin of the ocean. Was it whales who invented drumming?

Five minutes later, we would see two Orcas knife through the water. Then we understood. The humpback was warning her nearby pod and scaring off these skillful hunters who might have targeted her calf.

The next day, I travel up the ocean channel to an old crab apple grove where a spirit bear might appear. Patrick chooses a shorter trip. In my case, the spirit bear lives up to its other name – ghost bear – and stays invisible.

But Patrick sees a grizzly flop on her back to feed her triplets, so close a camera catches a drop of milk on her nipple when one cub tumbles off her belly.

I’m jealous. But an afternoon boat trip on the Pacific makes up for what I missed.

Patrick and I watch two humpbacks blow an elongated oval of bubbles to trap shrimp-like krill. The whales then rise to the surface through the centre of this airy net, their magnificent mouths wide open, catching their meal.

Looking down a whale’s gullet makes me shiver. Boy, how small I am!

On the day a storm blows in and the boats can’t go out, Doug Neasloss, the visionary behind the lodge, invites us into the Big House in Klemtu and tells us the history of his people and the work they’re doing to protect their homeland.

In 2012, they declared their territory off-limits to trophy hunting of bears (even though the B.C. gov’t allows it). Then, with other Coastal First Nations, they made a film about a grizzly skinned and left to rot in a field, head and paws carried out past a sign banning such hunting.

The timing of the film is sadly relevant. Just before its release this past September, The Vancouver Sun published photos of a defenceman with the NHL’s Minnesota Wild – how ironic is that name? – holding the severed head of a grizzly he shot in a rainforest estuary.

The tenderness the Kitasoo / Xai’xais feel for their culture and their home territory is palpable. We hear it in our skippers, who are all from Klemtu, and in Sierra, a grade 11 student who’s one of the lodge’s guides-in-training.

Every night in bed, she reads one of her people’s stories, and in her dreams, she’s in the story, walking among the humans and the creatures of the forest. The humans and the animals are talking to one another.

Many believe the Spirit Bear has special powers, she tells me.

Having sunk into the moss floors of the forests, having been held in the mind of a grizzly and the eye of a whale, I’m O.K., this time, to have missed Raven’s reminder of the ice age.

I’m sure there’s another reason for its creation, a reason that will sink in after I’m back home.

To many who live here, this singular being is an emblem of the sacredness of the rain coast and its vulnerability. They fear for potential oil spills in the area.

To them, this nightmare is a real and present danger as various levels of the Canadian government debate the sanctioning of oil tanker traffic through this delicate ecosystem.

They imagine the white bear soaked in oil, rivers and estuaries thick with crude muck, salmon thrashing in its slick, and orcas smeared with bitumen.

I’ve fallen under the spell of this rare sanctuary where salmon are born and die, where wolves have learned to swim and fish, and where mist may turn suddenly into the lumbering body of a mystic bear.

How diminished, how thin-hearted, how lonely we are as a species if there aren’t safe places in the world where the unique, the magnificent, can survive.

Postscript: The day after Patrick and I arrived home, Oliver from Germany, one of our companions who’d stayed an extra day at Spirit Bear Lodge, wrote that he did see a Spirit Bear. It stepped out of the moss-draped trees onto the stones of a river where he was set up with his camera on the other side. How thrilled he was. He’s seen what few people in his country, what few people in Canada or in the world, have ever seen. Check out thislink to his images

Lorna Crozier is a Canadian poet and holds the Head Chair in the Writing Department at the University of Victoria.

This essay originally appeared in Toque & Canoe, and in Counterpunch.[/private]