Light at the End of the World

Three Months on Cape St. James, 1941

by Hallvard Dahlie (orig from Raincoast 18, 1998) with notes from Jim Derham-Reid (last keeper on Cape St. James before automation)

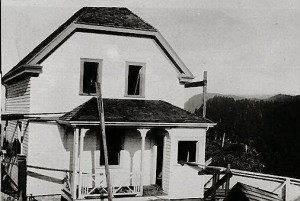

A strange interlude in my brief seafaring life took place in the fall of 1941, when I signed on as assistant lighthouse keeper at Cape St. James, a light perched on top of a three-hundred-foot rock at the very southern tip of the Queen Charlotte Islands. I had quit school earlier that year, at the age of sixteen, and found a job on the CGS Alberni, a lighthouse tender operating out of Prince Rupert. But when she had to go into dry dock at the beginning of September for a new wartime grey paint job and a bit of refurbishing, I chose to take a stint out at the lighthouse rather than scrape barnacles and paint for three months.

A strange interlude in my brief seafaring life took place in the fall of 1941, when I signed on as assistant lighthouse keeper at Cape St. James, a light perched on top of a three-hundred-foot rock at the very southern tip of the Queen Charlotte Islands. I had quit school earlier that year, at the age of sixteen, and found a job on the CGS Alberni, a lighthouse tender operating out of Prince Rupert. But when she had to go into dry dock at the beginning of September for a new wartime grey paint job and a bit of refurbishing, I chose to take a stint out at the lighthouse rather than scrape barnacles and paint for three months.

From a trip to the Cape earlier that summer, I knew full well how bleak and totally isolated this place was, and as we crossed Hecate Strait to anchor in the deserted whaling station of Jedway, [Rose Harbour -ed] I wondered what I had let myself in for. I remembered stories told by one of our deckhands about former keepers. One of them lived there with his companion, a gargantuan woman who hoarded all the food and released small amounts in exchange for sex, until finally starvation overcame his dwindling passion and he chased her out of the house with an axe. Then there was the story of the keeper who had gone mad one day and painted all the rooms in the house a bright marine red—walls and ceilings alike. These stories may have been exaggerated or fanciful, but they always reminded me of the lines from Gibson’s Flannan Isle,” one of the few poems I had liked back in grade nine:

And how the rock had been the death

Of many a likely lad–

How six had come to a sudden end

And three had gone stark mad.

So, as the Alberni rounded the last headland of Kunghit Island the next morning, and I saw the tower looming out of the haze, my stomach sank as it came home to me that this is where I was to live, with a complete stranger, for the next three months or so. There was certainly no way to escape from it, for the high rock on which the tower and dwelling were perched was separated from Kunghit Island by a narrow strait. Here the waters of the Pacific and Hecate Strait met in a steady roaring maelstrom that must be impossible to cross, and in every other direction there was nothing but open sea.

The captain had assured me that the present keeper, a Newfoundlander by the name of Herb Fitzgerald, was a kind and gentle fellow. But what would I do, I wondered, as we rowed in toward the landing, if he should suddenly go mad? Or if he was a bit fruity, like the chief steward I had worked under for a while on the Alberni?

I had seen the keeper briefly on that earlier trip as he checked over the supplies we were unloading from the workboat, but I hadn’t talked to him or looked all that closely at him. What I did remember was that he talked all the time, not to anyone in particular, but just talked, as though he had stored up a horde of words for a long time, and now had the chance to release them. As we rowed back to the Alberni, my rowing mate had said, “Look at that poor bugger, going back up to that tower all by himself.” There he was, climbing slowly up the long tramway, stooped over and limping a bit, steadying himself by holding on to the steel cable, and never once turning to look back at us, as though seeing us depart would confirm something he didn’t want to acknowledge.

Left: Alberni’s work boat. Below, Alberni off the

Cape.

And now he was busy loading supplies onto the tram car as I stood apart from him at the end of the jetty, watching my mates row back to the Alberni. The workboat rose high on the crest of a towering wave that had banked off the rocks, then disappeared into a deep trough, with only the head, shoulders and arms of Second Mate McKay visible as he stood in the stern controlling the steering oar. “Ye’ll be all right,” he had comforted me in his soft Scottish burr as they prepared to shove off. “I’ve known old Herb here for some while now, and he’s a right decent fellow. He’ll do nothing to harm you, and we’ll be back to pick you up in early December.” With that, I was struck by the full realization of my abandonment. I waved frantically as the workboat reappeared on the next crest, but no one noticed me, and the boat disappeared around the rock bluff.

All this time I had been vaguely aware of a chattering going on behind me, and now Herb’s voice came more clearly. “We’d better get a move on and get these supplies up, for it could be storming soon,” he was saying, straightening up from belaying a support rope around the cleats on the loaded tram car. “The glass was falling when I left the house, and storms come up awfully fast around here. We’ll come down later for the two fuel drums and the sacks of coal, but I don’t want our food to get wet.”

He had come down from the dwelling just as we arrived at the jetty, and when McKay introduced me, he looked surprised, as though he were expecting an older person. He was a tall, thin, grey-haired man with a slight stoop and a mouth that looked as though it was always grinning—which disconcerted me at first, for I thought he was always laughing at me, even when he was talking, which was most of the time.

“I didn’t know you were coming today,” he had explained, rattling on to McKay, “and I was sound asleep when your damn whistle woke me up. I was up all bloody night running the foghorn as well as tending the light, and I didn’t sleep hardly at all, so when there was no fog at daylight when I put out the light I thought I may as well sleep for a while because it isn’t that often I can sleep that long around here, and then that damn whistle woke me up and by the time I started the gas engine and got the tram down you guys were damn near in to the jetty already,” and he went on and on, just barely stopping when McKay told him I was to join him for the next three months.

And though he was puffing heavily as we walked up the long tramway, he kept talking all the way up, even when we stopped to rest so he could catch his breath. In fact, that first day he stopped only when he fell asleep. Even then I thought I heard some sounds coming from his room upstairs, but perhaps it was only the first of many strange noises I was to hear in that house. His sharp blue eyes pierced into mine as he spoke, as though he was afraid I might try to escape; fascinated by him and somewhat afraid, I don’t think I said more than half a dozen words to him that first day. I remembered parts of Coleridge’s poem, for it intrigued me in much the same way that “Flannan Isle” did, and like the Ancient Mariner, old Herb held me “with his glittering eye” and I could not “choose but hear,” for there was no escape.

There were, however, a number of specific tasks to learn and to do that first day, and here Herb was efficiency itself, wasting not a word or a motion. He showed me how to start the gas engine in the shed on top of the tramway and how to release and rewind the cable, so we spent a couple of hours hauling up the fuel drums, sacks of coal and remaining supplies. He demonstrated the operation of the foghorn, and most exciting to me, he showed me how to operate the light itself, situated in the concrete tower about a hundred and fifty feet beyond the house, at the very highest point of our rocky island.

“There are two things you must never allow to happen at a lighthouse,” he told me as we headed for the tower. “Never let the light burn during daylight hours, and never let the light stop during darkness, for both of these are signals of distress. Any ship that observes these conditions has to come in and check or radio someone for help, for they mean some sorts of emergency at the light.” He pulled open the heavy metal door and motioned me in ahead of him. “And if it isn’t an emergency, but just a case of our own carelessness, we really catch hell from the Department of Transport. I heard of a keeper down at one of the southern lights who got fired for being careless twice, so we can’t afford to make any mistakes.”

The ground level area of the tower was dark and cold and damp, and in its hollowness Herb’s voice ricocheted off the concrete walls as we climbed the steel steps to the next level. “This is what we call the Fresnel system,” he explained as he went up ahead of me. “and up here on the second level is where we keep the fuel tanks and winding mechanism. I’ll show you how to operate these in a minute, but let’s go up to the top level first, where I’ll explain the light itself and the kind of work we have to do during the day.”

We climbed the second set of steel stairs, and I was dazzled by the sudden light as I reached the upper level. For here there was nothing but glass—huge curved panels around the circumference of the tower top and massive prisms enclosing the light itself, and the late afternoon sun bathed everything in a brilliant translucence. Herb explained how the prisms gather the light produced by the mantles and concentrate it into a strong ray that passes through the central eye of the prisms, producing the powerful beam that revolves at a certain speed. “Every light on the coast revolves at a different speed,” he continued, “so if a captain has to check his position, and can get a glimpse of a light, he can check his directory of lights and figure out where he is. That’s why it is so important for us to keep these prisms absolutely clean, and all this surrounding glass, too, on both the inside and the outside,” and he opened a hinged glass panel so we could step out onto the surrounding catwalk.

“It’s not bad out here when it’s fairly calm, like today,” he said, grabbing the handrail and staring out over the sea, “But sometimes the damn wind almost blows you off as you’re washing these panels, so you have to be careful. Believe it or not, in the big storms we get out here, I’ve seen the spray from the waves blow right up and drench these windows.”

I looked down at the ocean, four hundred feet straight down below the west side of the tower, and even on this windless day, could see the billowing waves washing high up the side of the cliffs. I scanned the sea in all directions and far off to the west thought I saw a smudge of smoke. But I couldn’t be sure; it could have been a cloud or just a mirage. There was nothing else in any direction, and I realized that if we did run into any trouble out here, it could be ages before any help arrived. Off the south shore of our island was a narrow spit of rocks jutting into the sea, on which I saw movement.

“Them’s sea lions,” Herb explained, following my gaze. “There’s thousands of them, it seems, and you should hear the noise they make if something disturbs them. You’d think it was a bunch of babies howling, and in the middle of the night it can really it can really give you a fright. But let’s go back in, and I’ll show you how to light the lamp and keep it revolving.”

The lamp mechanism was really simple, consisting of two rather large mantles, much like the kind we had on our gas lamps back on the homestead, but it was fueled by kerosene rather than gas, kept in tanks on the second level. Beside the tanks was a drum with a winding mechanism and a thin wire cable wound tightly around it, whose end was attached to a heavy weight. “As soon as you light the lamp,” Herb explained carefully, “you have to come straight down here and release this catch so that the weight starts slowly unwinding the cable, which revolves the drum, which in turn through this set of gears rotates the light.” All that seemed pretty clear, but Herb went through the whole process again, so I paid close attention, thinking of his earlier warning about carelessness. “And we have to be sure to get up here every two hours to rewind the drum and pump up the pressure in these tanks, otherwise everything will come to a stop. I’ll come up with you tonight and watch you light the lamp, and make sure you do everything the right way, but after tonight you’re on your own, okay?”

So that’s how our routine was set up: I was to take the first shift, from six to midnight, then I would wake Herb and get to bed. Herb would extinguish the light at daybreak, and if there wasn’t any fog, he would go to bed for a couple of hours. Then we’d have our breakfast and go about our routines of the day.

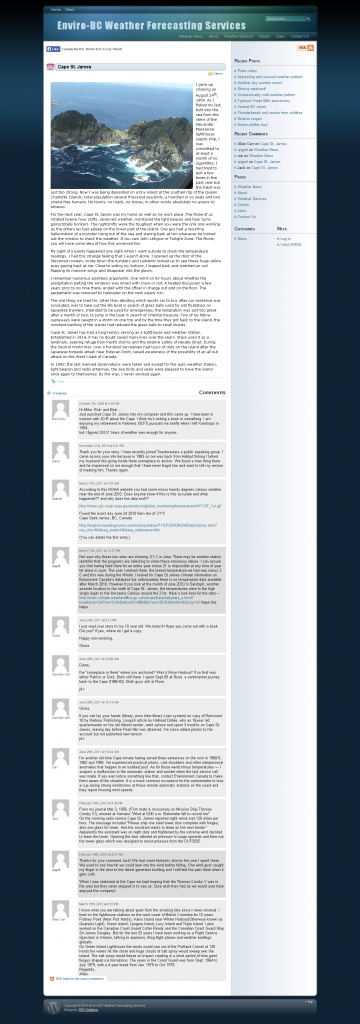

It was a ridiculously large house that the two of us occupied, built perhaps in the expectation that lightkeepers would sire many children, but the only large family I saw that summer was over at Triple Island, and that seemed to be the exception. Here there were some thirteen rooms on two floors, a half-basement, and a large covered verandah along the south wall [the east, ed] where the main entrance was. The front room had two large windows looking out on this porch and smaller window on the west wall, through which we could see the tower. The kitchen had one large window looking out to the east and north, and as I waited for Herb to come down for breakfast each morning, I would sit at the kitchen table looking out this window and scanning the coast along the east side of Kunghit Island for any sign of a ship, though I knew that the Alberni wouldn’t be along until early December.

(1925 re-build after the fire.)

(1925 re-build after the fire.)

“See anything yet, laddie?” were always the first words Herb said, his mouth turned up into more of a grin than usual, and he repeated these words every day that I was there, though as we got closer to December, I thought his grin grew less pronounced. He was always partially dressed when he came downstairs, carrying his checkered lumberjack shirt, his heavy black trousers held up over his winter underwear by a pair of bright red suspenders. He would yawn as he peered out of the window for a moment, brushing back his thinning grey hair with quick strokes of his hand, then disappear into a small washroom off the back of the kitchen, where we stored our barrel of rainwater for washing and cooking.

The house had no plumbing of any sort, and we took baths in the same galvanized washtub we used for our laundry, rare as either of these activities was. I can’t remember Herb ever washing his black trousers—by the end of my stay I’m sure they could stand by themselves—and I wasn’t much better. My bed had two sheets and a pillowcase and I would reverse top and bottom sheets, then turn them over and repeat the routine, turn my pillow [case] over when one side got unbearable dirty, then turn it inside out and repeat the routine. All this was done before any washing, and I felt pretty proud of my ingenuity.

And we had a precarious outhouse, the likes of which I had only seen once before, set at the very edge of a cliff beside a prospector’s shack up in the mountains above my home in the interior of BC. But because of the constant winds at Cape St. James, this one seemed even more risky. It was perched on the edge of a ravine a hundred feet or so from our back door and anchored with heavy cables to four concrete-embedded eye bolts. We could look through the hole straight down a couple of hundred feet to where the ravine angled out sharply to a rock outcropping. Sitting there as the roaring winds shook and buffeted this structure was an absolute assurance against constipation.

ON the west wall of the kitchen was a small cubby-hole, sort of like a pantry, with a chair and a small counter which served as a desk. Because we had only a coal oil lamp for light, it was in that room where we passed the long hours of the night, reading whatever we found in some boxes of old books and magazines an earlier keeper had left behind [Jimmy Kelly?] This room had one long, narrow window whose blind I always pulled down at night, because it was sort of scary to see my reflection looking back at from outside, the glass distorting my face and head as thought my hair was standing straight up.

With the wind almost always blowing, the house itself creaked and groaned, with noises seeming to come from all thirteen rooms, or from somewhere outside. I would step out from the cubby-hole into the darkness of the kitchen, hardly breathing, my heart pumping furiously, as I tried to assure myself that there was nothing to be afraid of. But what were those footsteps? Was it old Herb walking about directly over my head? No, his room was at the other end of the house, so I though about the keeper with the axe, and the madman who painted the rooms red, and I thought of “Flannan Isle” and wondered, was I going mad, too? Then the noises died away and I tiptoed back into my little well-lit room, trying to find comfort in the pile of magazines I had already thumbed through countless times, magazines like Liberty, Mechanics Illustrated, and a 1938 issue of Life, which showed Chamberlain returning from Munich and what I kept turning back to, an exposé of a Greenwich Village Artist’s model in various stages of undress.

Then my blood froze, for I heard someone outside, on the front porch, knocking on the window—or rather, scratching on the windowpanes. I though stupidly, why don’t they knock on the door? I moved silently to my little door, the lamp behind me throwing an enormous shadow on the kitchen wall, then I tiptoed slowly and cautiously to the door that led into the front room, from where I could look out the windows to the porch. I yelled in unmitigated panic, for there, up against the window, all dressed in white, was a figure waving its arms and bouncing up and down, as thought trying to find a way to get in. I could see him—or it—because the lantern we carried to the tower stood lighted on the porch, but I didn’t think I could be seen, for I was in darkness, and that gave me some courage. Then something else took over in my mind and said, there can’t be anyone else out there, we’re on an isolated rock hundreds of miles from any settlement, so where would anybody come from? And old Herb is sound asleep upstairs. And then I said to myself, of course, old Herb, and that white figure out on the porch immediately and with a stomach filling relief transformed itself into Herb’s winter underwear that he had washed that afternoon and hung on the line to dry, now frozen stiff by the icy winds.

It took me some time to work up the nerve to go out on the porch for the lantern and make my way up to the dark tower and tend the light, a scary enough task without the fear.

That was probably the longest night I spent in that house, and when I woke Herb, he said, “Did I hear someone yell in the night, or was I dreaming again? I have the damnedest dreams about this place.” I told him that he must have been dreaming, but he looked at me in a funny way, his grin more enigmatic than usual.

In that little cubby-hole, too, we kept our battery-operated radio, on which, every morning at nine o’clock, we received our daily instructions from the Department of Transport office in Victoria. These instructions were always written by the same person, whom I visualized as a rather frail old man, dressed in tweeds, with a pointed beard and thin lips that barely opened as he read, for the message would come through in a somewhat pinched and shaky tone: “Attention all lightkeepers on the Pacific Coast. Here are your instructions for today. Carry out instructions ‘A for Apple.’ I repeat, to all lightkeepers on the Pacific Coast, carry out instructions ‘A for Apple.’ This is the end of today’s message.”

There would be a bit of crackling static as the gentleman turned off the microphone, and we would immediately shut off the radio, for we knew that the C battery would not last forever and Herb always liked to listen to the six o’clock news before going to bed.

“A for Apple,” Herb told me, meant that we were to carry out normal operations for the light and foghorn, and these instructions didn’t change the whole time I was there. “If you ever hear instructions ‘B for Butter,” he explained, “that means that an enemy is approaching the coast in ships or submarines, and then we can’t have the light or any signals operating.” That sounded far more exciting to me, but it never happened while I was there. But as things turned out, if I had stayed one day longer, then ‘B for Butter’ would have been the order of the day, for the Alberni came to pick me up the day before Pearl Harbor.

To be more accurate, I should have said that the “A for Apple” message came not for as long as I was there, but as long as the radio’s C battery lasted, and I remember precisely the day it died for it was largely my fault. I had always been a baseball fan and it hadn’t been that long since my hero, Johnny van der Meer, had pitched two no-hit games in a row for the Cincinatti Reds. Now here it was October. World Series time.

So, in spite of Herb’s injunction to keep the radio off except for the news, I would surreptitiously turn it on after Herb had gone to bed, with the volume on low, to hear as much of the Yankees—Dodgers series as I could. I heard parts of games two and three, but the weakening battery had made each broadcast increasingly faint. Then, on the fifth day of October, I was listening to game four, with my ear pressed hard against the speaker, and it was two out in the ninth for the Yankees, with Brooklyn leading four to three. “It’s a swing and a miss for strike three!” I barely heard the announcer say, and then his voice rose in excitement, helping to compensate for the dying battery. “The catcher dropped the ball! Mickey Owen dropped the ball, and Heinrich is running to__” And that is all I heard for at that moment the battery went absolutely dead, and no amount of coaxing would bring it back to life. I had no idea, until the Alberni came two months later, what had happened in the rest of that game or who had won the World Series. [see end notes].

The days went by very quickly at first as the novelty of the place kept me intrigued, then more slowly as I waited for the Alberni to return. For Herb, all the days must have gone by too quickly. That first evening we had reached a unanimous decision, on the evidence of the meal Herb had prepared, that I would be cook, and his spirits had lifted visibly. “I’m so damn fed up with macaroni and canned tomatoes,” he complained, as I looked with some misgivings at the gooey red and white mixture on my plate, “that it won’t matter what you prepare, it’s bound to be an improvement.”

We had countless cans of powdered milk and I was good at making porridge, so that was our breakfast every morning, along with bread and jam and strong coffee. Herb had ordered generous quantities of chops, cutlets, ham steaks and other meat cuts that we stored in our basement, so our dinners didn’t stray much from the meat and potatoes variety, which suited both of us. Dessert was no problem, for Herb had ordered two or three cases of his favourite, canned pineapple, but one day I thought I would surprise him with a change—I cooked rice and raisin pudding. What I hadn’t realized was how uncontrollably rice would multiply when cooked, so for a few days we had to forgo the pineapple. I baked bread on two or three occasions, and once I made a batch of oatmeal cookies that not even the dampness of the whole Pacific Ocean could prevent from setting like concrete.

Our other tasks we organized according to the weather, and on the few fine days we had, we spent much of the time gathering firewood, for we had to use our coal sparingly. We picked up pieces of driftwood along the rocky shoreline, hauled them up on the tram car, then cut them into suitable pieces with a Swede saw and axe and stored them in the lean-to off the kitchen. The tide and wind normally brought in a large supply of driftwood every day, but once after a horrendous storm that lasted an entire day and night, we searched in vain. Every stick of wood, and even huge logs that had been wedged behind rocks far up the steep slopes, had been dislodged and carried out to sea.

When we felt we needed a break from this heavy work, we launched Herb’s small clinker-built rowboat to try our luck at fishing. Herb would deftly manipulate the boat into suitable spots and I would jig off the stern and generally catch one or two rock cod or red snapper. On one of these fishing trips, a whale surface close to our boat, then dived toward us and came up directly underneath us, lifting our small boat almost clear of the water. If Herb had not moved quickly to wallop it with his oar, we would certainly have capsized, and the whale’s wide tail flapped dangerously close to us as it shot away like a giant silvery dark arrow toward the swirling current of the narrow strait.

We were always careful in these dangerous waters to stay close to our shore, but one day the sea was unusually calm so we rowed across the strait to Kunghit Island and pulled out boat up on its sandy shore. All around us we found green glass balls, transparent and beautiful, ranging in from baseball size to something two or three times the size of a basketball. “These are Japanese fishing floats,” Herb explained, “broken free from their nets somewhere out there,” and he pointed his thumb toward the west. I wondered if they had floated all the way from Japan, or if they were harbingers of something closer to our shores. But like intruders coming upon some secret cache of treasures, we left them where we found them and headed back to our own island against a stiffening wind.

And one warm, windless Sunday afternoon we were up on the catwalk cleaning the windows of the tower, with Herb talking as much as ever, when over his voice I heard the sound of something else, like an engine, getting louder very quickly—and suddenly we ducked. For coming straight at us from the north, and only fifty feet or so above the tower, was a seaplane, dipping its wings in some kind of crazy salute. It dived down the south side of the island, sending hundreds of squealing, terrified sea lions off the rocks, and then it circled out to sea and came back for a landing in toward our jetty. We had seen the pilot waving at us as he roared past, and we saw the RCAF insignia on the wings and body, so we assumed it was from the air base at Alliford Bay, up at the north end of Moresby Island.

(Blackburn Shark III, crew of 3. from

(Blackburn Shark III, crew of 3. from

No. 6 (BR) Sqdn. RCAF Alliford Bay.)

I was quite excited about seeing someone else after all this time, and hurried down off the tower to go down to meet them. My imagination ran wild: Japanese fishing floats, radio going dead—had something happened that we didn’t know about? Or were they coming to get me, or perhaps they had a message from my family, for I hadn’t seen my mother before I came out here, but had only left a note on the kitchen table: “Have gone to Cape St. James for three months. Will be back in early December. Don’t worry.” As we waited at the top of the tramway for them to appear, Herb told me about a German fellow who was a keeper over at Ivory Island during the first war, and who was fired for being a security threat. “Maybe they thing you’re German instead of Norwegian,” he joked, “and they’re coming out to check on you.”

But it wasn’t nearly that dramatic. The crew was simply out on a routine patrol, had seen us out on the tower and decided on the spur of the moment to drop in on us and present us with a fresh salmon they had caught earlier that day on the west coast of Moresby. They stayed for an hour or so, had some coffee and a couple of my concrete cookies then took off up the east coast of Kunghit Island, leaving us to silence and ourselves. It was a welcome visit nevertheless, reminding us that we weren’t forgotten by the rest of the world after all.

But that Sunday was the last warm day of the fall, and the gloomy days passed slowly after that. The steady rain and wind kept us indoors most of the time, and the decreasing visibility made me feel more trapped and isolated than ever. Herb tried to lift my spirits one afternoon by giving me a haircut, but he was unpracticed and the scissors were dull, so what resulted was a straight line across the back of my head, a series of jagged steps up each side, just missing my ears, then a straight cut across the front that made me look like Ella Cinders. Will you do mine, now?” he asked when he had finished, and I said, “Sure, how do you want it cut?” and he said, “Off.” so that’s what I did, and for the next little while I don’t think either of us looked in the mirror much.

One morning in early December, Herb slept in longer than usual. I had finished eating my porridge and put the lid back on the pot to keep his warm, and was on my second cup of coffee when he came down. For once he didn’t look out the window or say, “See anything yet, laddie?” but went straight to the washroom. It was a gloomy morning, with clouds hanging low over Kunghit Island, and I had seen nothing in the hour or so I had been waiting for him. But when he came out of the washroom, cleanly shaven and washed, and dressed in his black trousers and checkered shirt, he said, “Well today’s the day. I feel it in my bones, and besides, I had a dream last night about a ship running aground on those rocks where all the sea lions are, so that must mean something. Maybe they need you back as quartermaster to steer the damn thing!” His grin lit up his face momentarily as he sat down and vigorously stirred his coffee, but his actions all seemed forced that morning. As I cleaned up the kitchen, he sat at the table, slumped over, just staring out the window, seemingly at nothing.

Sure enough, his bones were right. Just before lunch I detected a grey shape coming around the headland of Kunghit Island, barely visible through the haze and rain. It was still too far to determine whether it was the Alberni, and I didn’t want to get my hopes up too soon, so I didn’t look out again until I had prepared lunch and put it on the table. When I looked again there was no doubt, even though she was now all grey from stem to stern, where before her superstructure had been white and yellow. It nothing else, the huge plume of black smoke from her funnel gave her away, for only coal-burners produce such a volume of smoke, and the Alberni hadn’t yet converted to oil.

I was excited at the prospect of rejoining the crew, but I didn’t know what I should say to Herb, who scarcely touched his lunch, saying he wasn’t very hungry because he had had a late breakfast. He got up quickly from the table, grabbed his rain slicker, and said, without looking at me, “I’d better go out and start the gas engine. You’d better pack your things to send down on the tram car, because they’ll be rowing in within the hour.”

He knew full well that I didn’t have much to pack, but I knew fell well that he wanted to be alone for a while, so I packed slowly, folding each garment carefully, then stripped the bed and swept out my room. I put the two sheets and my pillow in a tub of cold water in the washroom, where only a miracle soap could ever make them white again. Then I stood in the kitchen and took a last look around, a bit smug, I suppose, over the fact that I had come through these last three months quite unchanged, except for my haircut.

But I couldn’t forget how I sat terrified in that little cubbyhole off the kitchen night after night, so afraid at the thought of having to walk up to that dark tower, flickering lantern in hand, not knowing what I might meet behind that heavy door. And then climbing the clanging steps up to the second level to pump up the tank and wind the weight mechanism, lifting the lantern above me to place it on the landing before I stuck my head up, in case there was something there. I remember how one night, not long after Herb’s underwear almost incapacitated me, the long blind on the tall, narrow window suddenly shot up without warning and I leaped out of my chair, paralyzed with fear, seeing my white face in the window staring back at me. No, there were things about Cape St. James lighthouse that I would not miss, and roused out of my memories by a loud, prolonged blast of the Alberni’s whistle, I put on my rain gear, grabbed my duffel bag, and went out to join Herb.

****************************

© Hallvard Dahlie. Raincoast Chronicles 18. 1998.

© Hallvard Dahlie. Raincoast Chronicles 18. 1998.

Photo credits:

Cape St. James Lighthouse: J. Osborne. DOT Radio Op.

Alberni: Gil Fetterly, DOT Radio Op. (Cape)

Alberni workboat: L/Keeper Charles A. G. Smith

1925 House: Northern Agency Pr. Rupert. 1925.

Blackburn Shark: Nat’l Archives

courtesy author Chris Weicht.

Hallvard Dahlie: Dr. H. Dahlie

*****************************

Notes from Jim Derham-Reid:

Now there are several interesting things about this account. One is that, by sheer co-incidence, the author was born on February 14th., 1925. Does that date ring a bell? Well, back a few chapters ago*, you must have read of the destruction of the old 1913/14 keeper’s house, and yes, it burned down on the very day that Hallvard was born. As I told him, the first 11 months of his life there was a crew on the Cape building a house for him to live in years later. (* see end of notes.)

Secondly, the matter of the fog horn. My friend, Ex-B.C. Lightkeeper, Chris Mills brought this to my attention, as I had evidently missed it in my original reading of this account. When Hallvard arrives on station, Herb says that he has been up half the night running the fog horn… but when the RCAF arrived in 1942/3 (see later account) there was no fog horn. Where did it go? We have no idea… Any theories welcome.

As to the stories about former keepers? ‘The fat lady and the axe man,’ and the ‘Mad painter’? Well, there exists no other reference to these tales, and I think they were no doubt just the sort of thing old timers told younger people as a matter of course; might have happened somewhere but not the Cape.

The strait between Kunghit Island and Hummock Island, (the name of St. James up to 1949)? Called in my day, the North Channel… “a maelstrom”? Well, only at tide-change times, or in storm conditions. At other times you could go across in a kayak, as I did with John How’s boat, or – even – paddle yourself over on an air mattress.

As far as the house being far too big…it was just a standard keeper house, built originally in 1913, and rebuilt (or built again if you will) from the identical plans, in 1925. The only ‘family’ who had ever occupied the place was in the period 1934-37 when Peter Doherty and his wife Emily were on station. They had two children. Also, the light assistants, one at a time, lived in the house as there was no other accommodation.

The 1941 World Series? (I knew someone would ask about this!) The results which Hallvard did not hear at the time due to the death of the radio’s C battery? The final game was the last in which Joe DiMaggio played prior to his joining the service following Dec 7. The outcome of the series? Yankees 4 Dodgers 1. Final game played in the Dodgers home, Ebbets Field, Brooklyn, Sunday October 5th.. After the war, DiMaggio came back to baseball, and later still, he was married to Marilyn Monroe…briefly it’s true, but hey! “t’is better to have loved and lost than never loved at all…” (Earl of Oxford but Shakespeare got the credit.)

Re Herb’s story about the keeper fired off his light during the Great War: Ivory Island keeper Mr. Reuter, 1904-1916. He was dismissed as he was considered an enemy alien. Sadly he had not been able to take out naturalization papers in 1914, as he could not leave his light.

Oh and by the way, the Blackburn “Shark” in the picture is not the one seen by Hallvard and Herb. No. 525 crashed on landing at Alliford Bay, Jul 19, 1940. The 3 man crew survived with minor injuries.

The Light on Eilean Mor

Lastly, Wilfred Gibson’s grim poem, Flannan Isle. This was one of the great Stevenson lights erected in the 19th century on the west, north and east shores of Scotland. Built in 1896 on the really remote Flannan Isles, WNW of Lewis, (about 7.5° W. Lat, 58.3° N. Long,) and staffed in ’99, it operated normally until the end of 1900, but when the steamer Hesperus arrived on Boxing Day for the relief, the three keepers had disappeared…from all the signs, about a week earlier:

“…The kitchen door was open, the fire laid out but unlit, the beds empty and crumpled.* The light itself was in perfect working order, the fuel supply full and the lamp freshly cleaned…” [*slept in but not made.]

The logbooks had been maintained until a week previously, and nothing was missing other than the keepers boots and foul-weather gear. Various rumours were circulated about the fate of the keepers but the Superintendent of Lights, Robert Muirhead, taking into consideration some damage to the landing area & the life-buoy stored 110 feet above the sea, missing, etc., thought that a freak-wave had taken all three men whilst they were securing the crate holding the landing ropes. Such waves are not uncommon on the west coast of Scotland, with nothing between the tiny isles and Iceland (NNW) or Greenland (NW) Mind you, at the Cape there was nothing to the west of us other than Japan, and there is a striking similarity between the two sites. The Flannan light was a 75′ tower at an elevation of 328′ above sea level. Cape was a smaller tower but at an elevation of 290 feet asl. On the other hand, our landing place was sheltered except in NE wind/sea conditions.

As for Gibson’s lines,

“…And how the rock had been the death

Of many a likely lad–

How six had come to a sudden end

And three had gone stark mad…”

well, other than the three lost keepers, put it down to poetic license. Still, Flannan was, not surprisingly, an unpopular light to serve on after this…

The title, Light at the End of the World? Jules Verne wrote an 1875 novel about another Light at the Edge of the World – Staten Island, Cape Horn. This title is one I have long used myself for the Cape. I believe Hallvard’s use of it only dates from the 1998 printing of his account.

The Light on Eilean Mor (Flannan Isles)

Joe Osborne’s photo of the Cape light

Joe Osborne’s photo of the Cape light

As Hallvard would have seen it in 1941.

3rd Order Fresnel Lens – identical to the Cape’s. This is the old lens from Point Atkinson, West Vancouver. (Courtesy Elaine Graham.)

(Photos inserted: jdr.)

Herb Fitzgerald was born in Newfoundland in 1891, and had served as a crewman on the tender Newington in the late 1920’s, along with Englishman, Frank Glinn. They would have been aboard when the vessel visited the Cape and around 1930, Frank ‘jumped ship’ to become Stan Lawrence’s assistant on the light, taking over briefly when the Lawrences left in 1931. When Frank left in ’32 he was replaced by Andrew A. Johnson, who had Herb as his assistant. Indeed, it is quite possible that Frank had Herb as his assistant when he took over from SF Lawrence! Since the department did not employ the assistants until the middle 1940’s – their salaries being paid by the keepers themselves – there is no official record, only what we glean from anecdotal sources. Anyway, Hallvard actually saw Herb in 1950, on the docks in Rupert, when he took his wife to see the Alberni. Herb died in 1976, in Terrace, aged 84, his notice lists him as “Sailor,” which of course, he had originally been. The information was filled in on the form by the Chief Nurse at Terrace hospital, so is not long on info.

Note. As indeed, assistant keepers were not paid by the department when Hallvard went ashore on The Rock, I asked him who paid him for the 3 month stint? “Ah well,” he said. “I was paid my quartermaster salary, just as if I was on the Alberni. I knew that Herb would have to pay me, otherwise, so it was a condition of my going ashore.”

* ref to section on the burning of the house in 1925. “Back a few chapters ago…” this was excerpted from the section in the Cape history entitled First Keepers.

© CSJG&CC. Cape Archival Collection.

jdr…2010

***********************

John.

John.

This photo is actually from 1957. I cropped it to take out a building to the left, which was the wartime Radio (Radar) shack and used after 1945 as the bunkhouse and radio (real radio) for the bachelor civilian radio Ops.

At this point I cannot recall if Halvard actually used the title I gave this – or is I simply decided to add it as a nice touch!

As I said, this version is sort of a non-pub account due to the photographs. 2008a is its file number in the RO CD.

*******************************

For further adventurous tales on Cape St. James click the photo below: