An island dispute of our own

Posted By Joshua Keating Wednesday, November 28, 2012 – 11:36 AM

It’s not quite the Senkakus, but Stephen Kelly highlights a long-festering territorial dispute between the United States and Canada:

Machias Seal Island is a 20-acre, treeless lump that sits nearly equidistant from Maine and New Brunswick. It, and the even smaller North Rock, lie in what local lobstermen call the gray zone, a 277-square-mile area of overlapping American and Canadian maritime claims.

Machias Seal Island is a 20-acre, treeless lump that sits nearly equidistant from Maine and New Brunswick. It, and the even smaller North Rock, lie in what local lobstermen call the gray zone, a 277-square-mile area of overlapping American and Canadian maritime claims.

The disagreement dates back to the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War. The treaty assigned to the newly independent 13 colonies all islands within 20 leagues — about 70 miles — of the American shore. Since Machias Seal Island sits less than 10 miles from Maine, the American position has been that it is clearly United States soil.

But the treaty also excluded any island that had ever been part of Nova Scotia, and Canadians have pointed to a 17th-century British land grant they say proves the island was indeed part of that province, whose western portion became New Brunswick in the late 18th century.

Perhaps more important to the Canadian case, the British built a lighthouse on Machias Seal Island in 1832, which has been staffed ever since. Even today, two lighthouse keepers are regularly flown to the island by helicopter for 28-day shifts to operate a light — even though, like every other lighthouse in Canada, it is automated. – Opinion Pages – NY Times

[private]

The New York Times Opinion pages Good Neighbors, Bad Border  Cartoon: John Malta

Cartoon: John Malta

By STEPHEN R. KELLY Published: November 26, 2012

AT a time when territorial disputes over uninhabited outcrops in the East China Sea have led to smashed cars and skulls in China, a similar, if less dramatic, dispute over two remote rocks in the Gulf of Maine smolders between the United States and Canada.

Machias Seal Island and nearby North Rock are the only pieces of land that the two countries both claim after more than 230 years of vigorous and sometimes violent border-making between them.

Except for the occasional jousting of lobster boats, this boundary dispute floats far below the surface of public or official attention, no doubt reflecting the apparent lack of valuable natural resources and a reluctance to cede territory, no matter how small.

But if we are unlikely to resort to arms anytime soon, the clashes in Asia have shown how seemingly minor border disputes can suddenly stoke regional and nationalistic tensions. Our relaxed attitude toward these remote rocks may well be a mistake.

While the United States and Canada have other maritime boundary disputes along their 5,525-mile border, the world’s longest, this is the only one left that involves actual chunks of land.

Machias Seal Island is a 20-acre, treeless lump that sits nearly equidistant from Maine and New Brunswick. It, and the even smaller North Rock, lie in what local lobstermen call the gray zone, a 277-square-mile area of overlapping American and Canadian maritime claims.

The disagreement dates back to the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War. The treaty assigned to the newly independent 13 colonies all islands within 20 leagues — about 70 miles — of the American shore. Since Machias Seal Island sits less than 10 miles from Maine, the American position has been that it is clearly United States soil.

But the treaty also excluded any island that had ever been part of Nova Scotia, and Canadians have pointed to a 17th-century British land grant they say proves the island was indeed part of that province, whose western portion became New Brunswick in the late 18th century.

Perhaps more important to the Canadian case, the British built a lighthouse on Machias Seal Island in 1832, which has been staffed ever since. Even today, two lighthouse keepers are regularly flown to the island by helicopter for 28-day shifts to operate a light — even though, like every other lighthouse in Canada, it is automated.

While abundant legal arguments surround Machias Seal Island, natural resources are far less evident. No oil or natural gas has been discovered in the area, nor has it had any strategic significance since it served as a lookout for German U-boats during World War I.

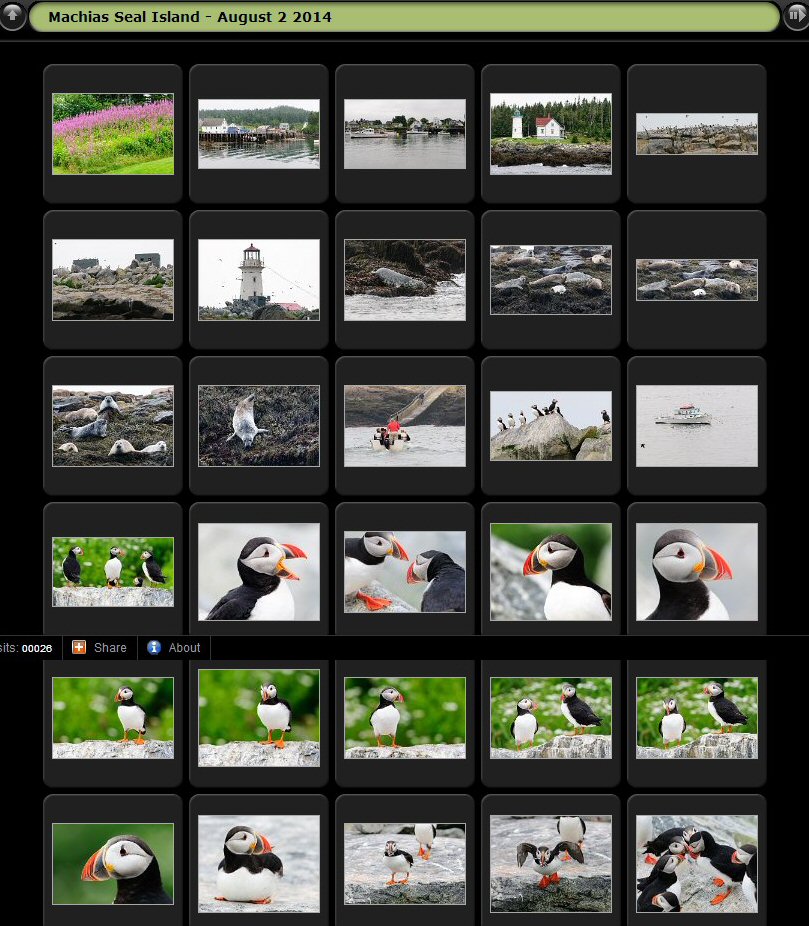

Tour boats from Maine and New Brunswick carry strictly limited numbers of bird watchers to the island to see nesting Atlantic puffins. And the surrounding waters contain lobsters that, thanks to different regulatory schemes and overlapping claims, have occasionally sparked clashes between Maine and New Brunswick lobstermen, although a bumper lobster crop this summer has slackened demand for gray zone crustaceans.

But the lack of hydrocarbons and the current lobster glut make this an ideal time to color in the gray zone.

The United States and Canada settled all their other maritime differences in the Gulf of Maine in 1984 by submitting their claims to the International Court of Justice for arbitration. They could have included the gray zone in that case, but did not. The Canadians had refused an earlier American arbitration proposal by saying their case was so strong that agreeing to arbitration would bring their title into question.

This attitude calls for re-examination. The fact that so little in the way of resources appears to be at stake, far from justifying the status quo, should be the main reason for resolving the issue. And for those concerned about blowback from “giving away” territory, letting the international court decide the case provides the most political cover.

As China and Japan can attest, border disputes do not go away; they fester. And when other factors push them back to the surface — the discovery of valuable resources, an assertion of national pride, a mishap at sea — the stakes can suddenly rise to a point where easy solutions become impossible.

Before that happens, we should put this last land dispute behind us, and earn our reputation for running the longest peaceful border in the world.

Stephen R. Kelly is the associate director of the Center for Canadian Studies at Duke University and a retired American diplomat who served twice in Canada.

A version of this op-ed appeared in print on November 27, 2012, on page A31 of the New York edition with the headline: Good Neighbors, Bad Border.

[/private]

[private] An island dispute of our ownPosted By Joshua Keating Wednesday, November 28, 2012 – 11:36 AM

It’s not quite the Senkakus, but Stephen Kelly highlights a long-festering territorial dispute between the United States and Canada:

It’s not quite the Senkakus, but Stephen Kelly highlights a long-festering territorial dispute between the United States and Canada:

Machias Seal Island is a 20-acre, treeless lump that sits nearly equidistant from Maine and New Brunswick. It, and the even smaller North Rock, lie in what local lobstermen call the gray zone, a 277-square-mile area of overlapping American and Canadian maritime claims.

The disagreement dates back to the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War. The treaty assigned to the newly independent 13 colonies all islands within 20 leagues — about 70 miles — of the American shore. Since Machias Seal Island sits less than 10 miles from Maine, the American position has been that it is clearly United States soil.

But the treaty also excluded any island that had ever been part of Nova Scotia, and Canadians have pointed to a 17th-century British land grant they say proves the island was indeed part of that province, whose western portion became New Brunswick in the late 18th century.

Perhaps more important to the Canadian case, the British built a lighthouse on Machias Seal Island in 1832, which has been staffed ever since. Even today, two lighthouse keepers are regularly flown to the island by helicopter for 28-day shifts to operate a light — even though, like every other lighthouse in Canada, it is automated.

Kelly reasonably suspects that the lack of natural resources in the region have made both sides reluctant to rock the boat by submitting their claims to the International Court of Justice for arbitration, as they have with other disputes. There’s simply nothing there worth the risk of losing the case and having to explain to voters why you “gave away” U.S. or Canadian territory. In any case, from the photos on Flickr it looks like the Canadian government has staked a pretty permanent claim to the island, so this one may be de facto settled.

Machias is the only U.S.-Canadian border conflict that involves land, but the sea border is disputed in a few places. Here’s Wikipedia’s list:

- Strait of Juan de Fuca 48°17?58?N 124°02?58?W (Washington /British Columbia) The middle-water line is the boundary, but the governments of both Canada and British Columbia disagree and support two differing boundary definitions that would extend the line into the Pacific Ocean to provide a more definite Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) boundary.

- Dixon Entrance 54°22?N 132°20?W (Alaska / British Columbia) is wholly administered by Canada as part of its territorial waters, but the US supports a middle-water line boundary, thereby providing the US more maritime waters. Canada claims that a 1903 treaty demarcation is the international maritime boundary, while the United States holds that the maritime boundary is an equidistant line between the islands that form the Dixon Entrance, extending as far east as the middle-water line with Hecate Strait to the south and Clarence Strait to the north.[2]

- Yukon–Alaska dispute, Beaufort Sea 72°01?40?N 137°02?30?W(Alaska / Yukon) Canada supports an extension into the sea of the land boundary between Yukon and Alaska. The US does not, but instead supports an extended sea boundary into the Canadian portion of the Beaufort Sea. Such a demarcation means that a minor portion of Northwest Territories EEZ in the polar region is claimed by Alaska, because the EEZ boundary between Northwest Territories and Yukon follows a straight north-south line into the sea. US claims would create a triangular shaped EEZ for Yukon. This is mainly an Alaska-Yukon dispute.

- Northwest Passage; Canada claims the passage as part of its “internal waters” belonging to Canada, while the United States regards it as an “international strait” (a strait accommodating open international traffic).

The last two might get a bit more controversial as resource competition in the rapidly melting Arctic heats up.

[/private]