Originally I had this article titled as Lighthouse Time referring to the time we were required to be at work on the station. Lighthouse Time-Keeping (leading up to automation) is a better phrase as it reflects punching the clock, etc. which we did not actually have do on a lighthouse. Someone was always there. You never left a lighthouse alone.

Originally I had this article titled as Lighthouse Time referring to the time we were required to be at work on the station. Lighthouse Time-Keeping (leading up to automation) is a better phrase as it reflects punching the clock, etc. which we did not actually have do on a lighthouse. Someone was always there. You never left a lighthouse alone.

On the lighthouse we worked to get the job done. When it was done we could relax. We were on watch all the time.

In the early days (1800s – 1950s) the lighthouse was a one family station and if an assistant was required for heavy work then it was up to the keeper to hire a person from the local community using his own wages to pay the person. The keepers hours of duty were long and hard and were broken only when the wife was free to help out. Two man and/or family stations were only on very isolated stations with keepers on duty approximately twelve hour shifts but usually longer. Actually, at that time, no shifts were set down on paper – the station had to be manned no matter what.

In the 1950s to 1970s the stations with more duties, equipment, or isolation had an extra man so there were one-, two- and three-man stations. These people were on duty at differing hours. A one-man station required the keeper to sometimes sleep in the engine/fog alarm room when heavy fog was prevalent for days on end. In the mid 1960s the two-man stations had a shift time of twelve hours each man and three-man stations eight hours each. The early 1970s saw some automated equipment installed and most three-man stations reduced to two-man and a susequent increase in the number of hours on duty without an increase in pay.

In the 1950s to 1970s the stations with more duties, equipment, or isolation had an extra man so there were one-, two- and three-man stations. These people were on duty at differing hours. A one-man station required the keeper to sometimes sleep in the engine/fog alarm room when heavy fog was prevalent for days on end. In the mid 1960s the two-man stations had a shift time of twelve hours each man and three-man stations eight hours each. The early 1970s saw some automated equipment installed and most three-man stations reduced to two-man and a susequent increase in the number of hours on duty without an increase in pay.

Late 1970s brought more talk of automation, more equipment, especially station monitoring equipment for automation, but no increase in the keeper’s pay. In fact the first closing of some stations was started, automation equipment was put in place and keepers were ignored.

Finally by the mid 1980s a job description was given to the lighthouse keepers and this would be what their wages were based on – more duties, more pay.

Keepers were requested to submit a list of the duties they performed and the time involved. But only Coast Guard related work was to be on the list. All the extra work the lightkeeper did was not recorded – jobs such as weather reporting, sea water samples, search and rescue, bird and animal surveys, pollution watch, radio watch, etc. This, according to the Coast Guard was not the job of a lighthouse keeper.

Keepers were requested to submit a list of the duties they performed and the time involved. But only Coast Guard related work was to be on the list. All the extra work the lightkeeper did was not recorded – jobs such as weather reporting, sea water samples, search and rescue, bird and animal surveys, pollution watch, radio watch, etc. This, according to the Coast Guard was not the job of a lighthouse keeper.

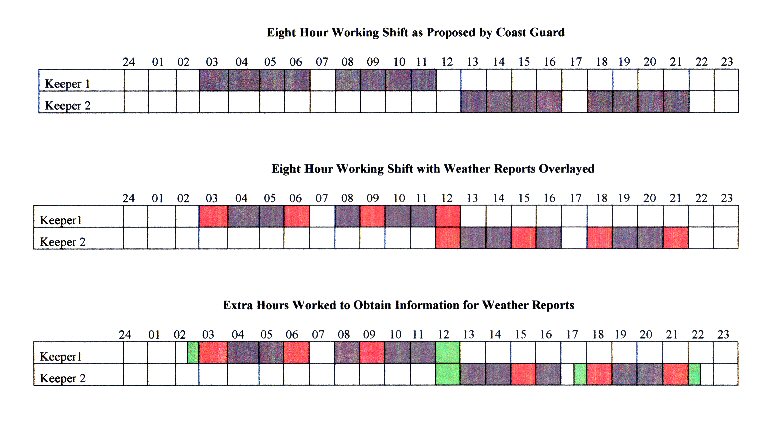

Again in the mid 1980s, automation in Ottawa computers and on the lights designated that we had to have hours of work laid down. Up to that time we were paid a yearly wage divided by the number of government paydays in a year (52). This gave us our bi-monthly wage. Divided by the number of hours we were on duty (for seven days a week you must remember), this worked out to very much less than the minimum wage at the time. Finally the government worked out that we would all have an eight hour shift each, during daylight hours and they worked it out this way:

As you can see the by the first table the shifts were 8 hours long in two periods as we were supposed to ignore the station during our one hour break at lunch and breakfast and supper.

The second table shows that weather reports did not fit into this shift pattern at lunchtime.

The third table shows the extra quarter hour (or half hour, depending on the intensity of weather) we used to make the observations and record all afterwards. The result was a normal nine- to ten-hour day but we were only listed as working eight.

What the government did not include was overtime! We had an eight hour shift to work. Finished! They did not consider the times when we were phone in the night for weather reports, where one had to dress, go outside, read the barograph and write-up the weather; or the nights where we baby-sat a boat in distress because Coast Guard radio was tied up with so many incidents because of bad weather; or the nights the engines shut down because of bad fuel delivered to us; or the time the main light blew out twice in a row; or the time the battery went dead on their automatic engines and shut down the station (the battery controlled the control panel) – I can list hundreds of times we worked through the nights, but all on an eight hour shift!

You will notice on the pay stub (left) the highlighted number 56 under “Hours of Work”. This is eight hours a day for seven days (8 hours X 7 days = 56 hours). You can also see by the shift chart that daylight hours (which were imposed to stop us collecting shift differential1) were an impossibility unless you were working in the summer above the Arctic Circle!

But, there was a good side. We worked as we wished. No office supervisor and no daily logging in and out. We could work twelve hours here and then go fishing for four hours, always mindful of the radio, the weather, engines, fog, and the light. We could work a morning shift and spend the next eight hours unloading a supply ship (no overtime) and then hit the sack. Next day we could take it easy! Only the weather reports at 3AM , 6AM, 9AM, Noon, etc.

But then the Coast Guard decided that we had to report exactly what we were doing! They issued us with log books and a new set of rules and we were supposed to log everything we did during our shift!

Well we filled the books with every little detail we performed. Contrary to our job description we included all the local, marine, synoptic, special and extra weathers. All the radio contacts, all the ship contacts, all the jobs done and listed every minute of the shift. We filled reams of books and sent them into the office every month. It didn’t help us, didn’t help them, but gave us an extra entry in the logbook “0900-0910 Filling out logbook”!

Well we filled the books with every little detail we performed. Contrary to our job description we included all the local, marine, synoptic, special and extra weathers. All the radio contacts, all the ship contacts, all the jobs done and listed every minute of the shift. We filled reams of books and sent them into the office every month. It didn’t help us, didn’t help them, but gave us an extra entry in the logbook “0900-0910 Filling out logbook”!

Present day (November 2006) the Coast Guard removed most of the foghorns (no monitoring), lowered or changed the intensity of the lights, removed range lights, removed radio beacons and their towers, removed weather equipment such as barometers, wind recorders, etc., and removed from the lightkeepers duties most weather reporting details so that they have become glorified groundskeepers.

But rest assured, as long as the government lets them remain on duty, they will come to your assistance with a radioed weather report, a can of gas or a friendly hello. God Bless all lighthousekeepers!

*************************************

FOOTNOTES:

1Shift Differential – Additional pay for work regularly performed outside normal daytime hours, usually defined as before &AM and after 6PM.